My own notes written while going over the RHCSA course outline. Though the list of requirements may look daunting, give yourself a few weeks and many of these concepts trickle into your brain through practice. I didn't conjure these notes from thin air; here are other great guides for the RHCSA exam:

- The official Red Hat labs teach you many important concepts without you having to configure an environment.

- CSG on Youtube gently walks you through each of the requirements for RHEL8 on video. Many of my notes simply jot down his working. Buy him a coffee!

- The RHCSA exam guide by Ashgar Ghori gives a very detailed overview of the exam - both abstract and practical - if you can get your hands on it.

- Red Hat Linux 9, a Packt Publishing book quite dense with useful information.

- Eddie Jennings on Youtube teaches some concepts well and provides a more recreational tone to his videos.

- Public study guide for RHCSA which has notes for each unit seperated into folders. Anyone can submit more notes.

- Practice questions when you are ready. The book is free for a month with a kindle unlimited trial.

Did this Gist help you? Give it a 🌟 on Github to make me happy.

| Section | Objectives | Syllabus |

|---|---|---|

| Access the exam | Interrupt the boot process | x |

| Change the root password | x | |

| Understand and use essential tools | Access a shell prompt and issue commands with correct syntax | x |

| Use input-output redirection (>, >>, | , 2>, etc.) | x | |

| Use grep and regular expressions to analyze text | x | |

| Access remote systems using SSH | x | |

| Log in and switch users in multiuser targets | x | |

| Archive, compress, unpack, and uncompress files using tar, star, gzip, and bzip2 | x | |

| Create and edit text files | x | |

| Create, delete, copy, and move files and directories | x | |

| Create hard and soft links | x | |

| List, set, and change standard ugo/rwx permissions | x | |

| Locate, read, and use system documentation including man, info, and files in /usr/share/doc | x | |

| Create simple shell scripts | Conditionally execute code (use of: if, test, [], etc.) | x |

| Use Looping constructs (for, etc.) to process file, command line input | x | |

| Process script inputs ($1, $2, etc.) | x | |

| Processing output of shell commands within a script | x | |

| Processing shell command exit codes | RHEL 8 | |

| Operate running systems | Boot, reboot, and shut down a system normally | x |

| Boot systems into different targets manually | x | |

| Interrupt the boot process in order to gain access to a system | x | |

| Identify CPU/memory intensive processes and kill processes | x | |

| Adjust process scheduling | x | |

| Manage tuning profiles | x | |

| Locate and interpret system log files and journals | x | |

| Preserve system journals | x | |

| Start, stop, and check the status of network services | x | |

| Securely transfer files between systems | x | |

| Configure local storage | List, create, delete partitions on MBR and GPT disks | x |

| Create and remove physical volumes | x | |

| Assign physical volumes to volume groups | x | |

| Create and delete logical volumes | x | |

| Configure systems to mount file systems at boot by universally unique ID (UUID) or label | x | |

| Add new partitions and logical volumes, and swap to a system non-destructively | x | |

| Create and configure file systems | Create, mount, unmount, and use vfat, ext4, and xfs file systems | x |

| Mount and unmount network file systems using NFS | x | |

| Configure autofs | RHEL 9 | |

| Extend existing logical volumes | x | |

| Create and configure set-GID directories for collaboration | x | |

| Configure disk compression | RHEL 8 | |

| Manage layered storage | RHEL 8 | |

| Diagnose and correct file permission problems | x | |

| Deploy, configure, and maintain systems | Schedule tasks using at and cron | x |

| Start and stop services and configure services to start automatically at boot | x | |

| Configure systems to boot into a specific target automatically | x | |

| Configure time service clients | x | |

| Install and update software packages from Red Hat Network, a remote repository, or from the local file system | x | |

| Work with package module streams | RHEL 8 | |

| Modify the system bootloader | x | |

| Manage basic networking | Configure IPv4 and IPv6 addresses | x |

| Configure hostname resolution | x | |

| Configure network services to start automatically at boot | x | |

| Restrict network access using firewall-cmd/firewall | x | |

| Manage users and groups | Create, delete, and modify local user accounts | x |

| Change passwords and adjust password aging for local user accounts | x | |

| Create, delete, and modify local groups and group memberships | x | |

| Configure superuser access | x | |

| Manage security | Configure firewall settings using firewall-cmd/firewalld | x |

| Create and use file access control lists | RHEL 8 | |

| Manage default file permissions | RHEL 9 | |

| Configure key-based authentication for SSH | x | |

| Set enforcing and permissive modes for SELinux | x | |

| List and identify SELinux file and process context | x | |

| Restore default file contexts | x | |

| Manage SELinux port labels | RHEL 9 | |

| Use boolean settings to modify system SELinux settings | x | |

| Diagnose and address routine SELinux policy violations | x | |

| Manage containers | Find and retrieve container images from a remote registry | x |

| Inspect container images | x | |

| Perform container management using commands such as podman and skopeo | x | |

| Build a container from a Containerfile | RHEL 9 | |

| Perform basic container management such as running, starting, stopping, and listing running containers | x | |

| Run a service inside a container | x | |

| Configure a container to start automatically as a systemd service | x | |

| Attach persistent storage to a container | x |

While this concept is taught in Section 5: Interrupt the boot process in order to gain access to a system, it is generally known that this process is needed in order to gain access into the exam environment. It is very important and without it, you can't gain any marks.

In order to interrupt the boot process and reset the root password, use the following commands:

reboot # restart the device

## On the loading screen, repeatedly press ⬆ to stop the OS booting automatically.

## press 'e' to edit the boot sequence

## edit the second to last line to include rd.break

## press ctrl-x to execute the new boot sequence

## in the new shell:

mount -o remount rw /sysroot

chroot /sysroot

passwd ## set password

touch /.autorelabel

exit

rebootA variety of essential knowledge is needed to know one's way around a linux terminal. A basic bash shell command:

ls -l /home/This command has three portions, each with a different purpose:

lsis the command executed-lis an option argument/flag, providing extra context for the command/home/is a target argument, pointinglsto a specific place

A few basic commands are dedicated to manipulating files and dirs. They don't have much depth and are fast to get the hang of.

lslist directoriescdchange directorytouchcreate an empty filemkdircreate an empty directorymvmove a file or directorycpcopy a file or directory (cp -rto recursively copy a directory and its contents)rmremove a file or directory (rm -rfor dirs)

While you can manipulate files using non-interactive commands such as sed, you can interactively edit a file using vim. To learn the basics of vim use the command vimtutor.

vimtutor

vim file.txtWhile there are great online resources for learning, at certain points looking in is more useful than looking out. Below are tools built into Red Hat linux to help you find documentation.

mansearches for a manual on a command. You may need to runmandbto refresh your system manuals./usr/share/doccan begrep'd for information<command> --helpoften gives some basic usage informationinfowhatisapropos

Use man to find out what the rest do.

Often times when using linux shell commands, you will want to chain the output of one command elsewhere rather than just print it out on the screen.

ps auxprints process information to screenps aux > filesends ps info to fileps aux >> fileappends info to fileps none 2> filesends error log to fileps aux | grep /usrsends ps info to grep, which prints lines containing/usrto screengrep /usr < filegreps usingfileas input

grep searches input files to match for patterns. Patterns are matched using regular expressions. At its simplest, grep for a string you want to find.

cat bee_movie_script | grep aviation

According to all known laws of aviation,You can also pass various flags to make grep more versatile. Here, the -i flag makes the search case-insensitive. the -C1 flag adds 1 line of extra context around each instance of the found string. They are combined into a single -iC1 flag which grep can interpret as if the flags were separate.

cat bee_movie_script | grep -iC1 aViAtiOn

According to all known laws of aviation,

there is no way a bee should be able to fly.For a deeper dive into grep and regex, visit the GNU grep manual and hands-on regex lessons in regexone.

Many computer files are zipped up in archive files. The files are often compressed in size and more portable than a regular folder of files. Over time, various different standards have been used for file archiving. Below are some of the more popular archiving tools.

- tar: a sensible default archiving utility.

tar --extract --file archive.tar- extracts contents from archive.tartar --create folder/ --file archive.tar- compresses folder/file to archive.tar

- gzip: a cosier archiver. often compresses much more than .tar, but it can't compress folders.

gzip file- compresses file to file.gzgunzip file.gz- unzips gzip filegzip folder.tarcompresses folder using .tar as a proxy

- bzip2: alternative to gzip

- star: alternative to tar

Sometimes you may need to reference a file in two locations. By default, each file you make is hard-linked to a set of inodes in the file system. You can make another hard link to the inodes:

touch file

ln file /tmp/sameFileYour file is now in two locations.

Instead of hard-wiring the file, you may just want to point the second location to the first location - kind of how a shortcut works in Windows. To do this, pass the -s flag.

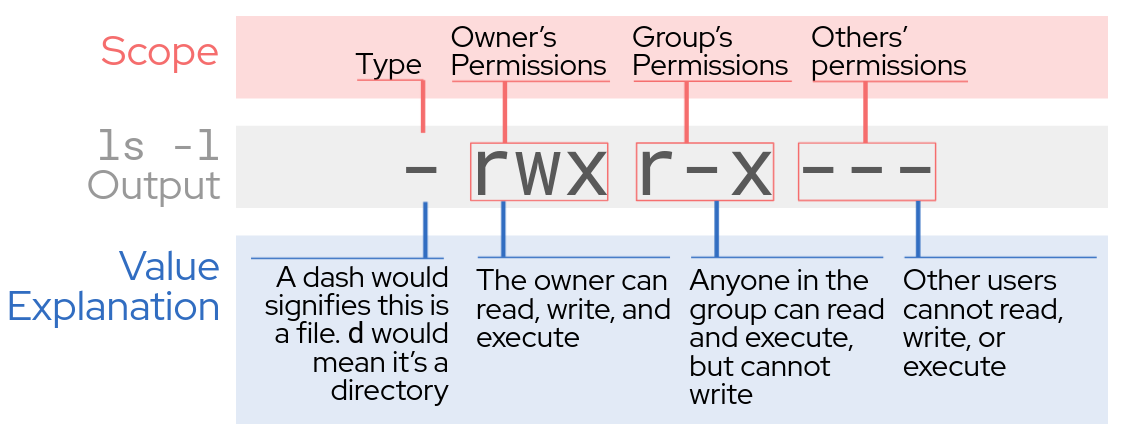

ln file -s /tmp/sameFileFile permissions work in three modes and three scopes. The graphic below describes each.

To view permissions in your current directory, use ls -l.

root@rhel:/srv# ls -l

total 8

drw-r-----. 2 root root 94 Dec 22 15:47 proprietary

-rwxr-x---. 1 root root 54 Dec 22 15:47 status.sh

-rwxr-x---. 1 root root 126 Dec 22 15:47 tasks.txtFor modifying these basic permissions, use chmod.

To allow others to read and execute status.sh, use the command chmod o+rx status.sh

You can use the binary representation of all permissions to make the process more straightforward. The graphic below describes this process.

Use chmod to give absolute permissions:

root@rhel:/srv# chmod 774 status.sh

root@rhel:/srv# ls -l status.sh

-rwxrwxr--. 1 root root 54 Dec 22 15:47 status.sh

root@rhel:/srv# Use chown to change who owns a file:

root@rhel:/srv# chown user file.txt # change owner to 'user'

root@rhel:/srv# chown -R user dir/ # recursively change owner of whole directoryIn many system administration scenarios, you don't have physical access to the computer you're working on. With the rise of cloud computing, this is more true now than ever.

Remote into another shell using the secure shell protocol.

# ssh <user>@<ip>

ssh root@localhost

ssh user@192.168.0.1 -p 2022 # enter a specific port

ssh root@localhost -i cert.ppk # a secure system user a ppk certificate to loginOnce you are inside a multi-user system, switch users using su.

sudo su # switch to root

su <username> # switch to specific user

su - <username> # switch to user and navigate to their home directoryBecause shell scripts are simply an extension of commands you type into the terminal each day, shell scripts induce many of the bash commands you already know and love.

Bash variables are inferred and declared like in many other languages. To refer to them later in the script use $.

#!bin/sh

hello="Hello world!"

echo $helloThe first feature of bash you likely don't use when using the interpretive shell are conditional statements. However, you can use them directly in a shell if you want:

if [ "1" == "1" ]; then echo 'true'; fiConditions are wrapped in [ angular brackets ]. They have an if block and a then block, and end with fi.

#!/bin/bash

VAR1="Hello"

if [ -z ${VAR1} ]; then

echo 'true';

else

echo 'false';

fiThe following script uses a conditional flag. -z checks if the variable is empty.

#!/bin/bash

## file.sh

VAR1="123"

if [ -z ${VAR1} ]; then

echo "var is empty";

else

echo "var: ${VAR1}";

fi[root@localhost ~]# sh file.sh

var: 123

[root@localhost ~]#A list of conditional flags can be found on the GNU bash page

Once you are comfortable with the concept of [ conditions ], try wrapping your conditions in [[ two brackets ]]. This syntax is a bash extension of shell scripting, and has a few quality of life improvements. Read this SO page for more info.

Another feature of bash script is the use of positional arguments.

#!/bin/bash

## file.sh

if [ -z $1 ]; then

echo "var is empty"

else

echo "var: $1"

fiInstead of hard-coding the variable value, $1 takes the first argument passed when the script is invoked in the command line. If you want to pass more than one variable use $2 $3...

[root@localhost ~]# sh file.sh

var is empty

[root@localhost ~]# sh file.sh 123

var: 123

[root@localhost ~]#Another important part of scripting is leveraging loops. Below are some common examples of bash loops.

#!/bin/bash

for i in 1 2 3 4 5

do

echo "Hello $i"

doneThis prints out what you'd expect:

Hello 1

..

Hello 5

In modern bash, you can use curly braces to induce a {start .. end .. increment}

#!/bin/bash

for i in {0..10..3}

do

echo "Hello $i"

doneHello 0

Hello 3

Hello 6

Hello 9

Because bash can infer variable types, it can also detect when your variable is a path to a folder. A * is a regex which helps select all files in a folder.

#!/bin/bash

directory=/tmp/files

mkdir $directory

for i in {1..5};

do

touch "$directory/$i.file"

done

for file in "$directory/*";

do

echo $file

done

rm -r /tmp/files[root@localhost ~]# sh loop.sh

/tmp/files/1.file /tmp/files/2.file /tmp/files/3.file /tmp/files/4.file /tmp/files/5.fileTo process the output of a shell command within a script, use $() to open a subshell.

#!/bin/bash

IFS=\n # special variable, changes delimiter to new line

for i in $(ps | grep bash);

do

echo $i

done[root@localhost scripts]# sh file.sh

1977 pts/0 00:00:00 bashYou should be aware that an exit code 0 means successful exit, while an exit code of 1, 2, or anything else implies an error code. To check the exit code of a previous command use $?.

[root@localhost dir]# ls .

1.file 2.file 3.file 4.file 5.file

[root@localhost dir]# echo $?

0

[root@localhost dir]# ls 123

ls: cannot access '123': No such file or directory

[root@localhost dir]# echo $?

2In a script, you would use a specific exit code on a certain condition. Then, you would document what each exit code means. Use exit n to exit your code at that point in the script, with that specific exit code.

Although a lot of problems can be solved with turning things on and off (taught below), deployed systems should have downtime minimised. Operating on running systems is a very useful skill.

sudo shutdown nowsudo rebootpress-the-power-button

[root@localhost ~]$ systemctl get-default

# graphical.target

[root@localhost ~]$ systemctl list-units --type target # lists secondary targets for graphical.target

UNIT LOAD ACTIVE SUB DESCRIPTION

basic.target loaded active active Basic System

cryptsetup.target loaded active active Local Encrypted Volumes

getty.target loaded active active Login Prompts

graphical.target loaded active active Graphical Interface

[root@localhost ~]$ systemctl set-default multi-user.target

[root@localhost ~]$ shutdown -r now

### You will reboot in a non-graphical mode.See section 0.

top: identify processes.- cycle what's at the top by using

<and>.

- cycle what's at the top by using

ps -ef: snapshot oftop.kill <pid>: terminate a process. find the PID fromtop.kill -9 <pid>: kill unresponsive process.

Processes have various attributes which determine how they interact with other processes on the system. An example of this is niceness, shown as NI in top. To change these values in real-time on running processes, use the chrt command.

chrt -m: shows each available policy, with min/max priority values.chrt -b -p 0 <pid>: sets scheduling policy to-batch with a-priority of 0 .chrt -p <pid>: get scheduling info about a process.

A system daemon, tuned, automatically monitors and tunes system performance. Very cool!

dnf install tunedsystemctl enable tunedsystemctl start tuned

Once tuned is running, you can administer it using tuned-adm. Use it to manually set different tuning profiles.

tuned-adm active: prints active profile.tuned-adm list: show all available profiles.tuned-adm profile <profile>: switch to specific profile.tuned-adm recommend: prints recommended profile.

Various programs send helpful log files. If you are debugging this can be very handy.

Logs are located in /var/log/. They may all be useful depending on the application, but here are some generally interesting ones.

/var/log/secure: authentication logs./var/log/messages: service messages, daemons, systemd./var/log/audit/audit.log: SELinux logs.

There are various ways to inspect boot logs;

systemd-analyze blame: view process boot times.journalctl: detailed low-level boot processes.man journalctlshows other useful features.

To preserve logs past reboot:

[root@localhost ~]$ mkdir /var/log/journal

[root@localhost ~]$ echo "SystemMaxUse=50M" >> /etc/systemd/journald.conf ## otherwise it grows indefinitely

[root@localhost ~]$ systemctl restart systemd-journal # now logging in /var/log/journal!Thanks to the spooky powers of systemd, we can manage network services the same way as any other service.

systemctl enable --now sshd: persistently enable and start service.systemctl status sshd: check status of service.systemctl mask sshd: invalidates service.unmaskto undo.

If you have two systems and need to transfer files, use scp.

scp <file> <user>@<ip>:<file>: secure copy to other machine.scp <user>@<ip>:<file> .: secure copy from other machine to current folder.

Linux partitions are a larger-size topic than likely fits into this syllabus. Without explaining the theory, the basics for creating a partition are below:

lsblk: list partitions. You want your drives (sdbfor example) to expand out tosdb1,sdb2etc.fdisk -l: more in-detail partition informationfdisk /dev/sdx: manage your partitions. pressmfor details.g,n,pandware good lettersmkfs.ext4 /dev/sdxyyou need to ma-ke-a-file-system from your partition before you can...mount /dev/sdxy /mnt...mount your new partition

man fdisk- For some finnicky tasks like resizing you can make use of

GNOME Disksfrom the GUI.

Other utilities such as resize2fs are available, but potentially out of scope. Follow this link to learn more.

While disks are represented as /dev/sdx on the filesystem (physical volumes), there are ways to string these together to be more user friendly (more logical).

Here is an image which explains the difference between physical volumes, abstract volumes and volume groups.

The following commands are the bare-bones for creating a logical volume group with multiple logical volumes. A more in-depth explanation can be found on Falko Timme's beginner's guide to LVM.

lsblk

## ... sdb, sdc, sdd, ...

fdisk /dev/sdb # KEYS: m , n , p , ENTER , ENTER,

# repeat for sdc, sdd

## Creates physical volumes

pvcreate /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1 /dev/sdd1

# pvremove /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1 /dev/sdd1

# pvdisplay # list physical volumes

## Creates volume group fileserver and adds physical volumes to it

vgcreate fileserver /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1 /dev/sdd1

# vgdisplay # list volume groups

# vgscan # in-depth group scan

## Creates logical volumes within the volume group

lvcreate --name media --size 5G fileserver

lvcreate --name backup --size 5G fileserverlvscan: shows an brief of your logical volumes.vgs: overview of volume groups.

At this point, your logical volumes can be treated pretty much like physical volumes. Make the volume into a filesystem and mount it:

mkfs.ext4 /dev/fileserver/media

mkfs.xfs /dev/fileserver/backup

mkdir /var/media /var/backup

mount /dev/fileserver/share /var/share

mount /dev/fileserver/backup /var/backup

df -h

# Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

# /dev/sda2 19G 665M 17G 4% /

# /dev/sda1 137M 17M 114M 13% /boot

# /dev/mapper/fileserver-backup

# 5.0G 144K 5.0G 1% /var/backup

# /dev/mapper/fileserver-media

# 5.0G 33M 4.9G 1% /var/media

#Although backup is not set up (with RAID) to actually save the media folder, a logical volume has been made. For a deep dive follow the link above about LVM beginners guide.

Partitions on a hard drive are permanent, but their mount points are reset each time the system reboots.

The system file /etc/fstab is read each time the system boots, so it's a great place to permanently mount drives.

Warning: if you set your fstab incorrectly, or later unmount a drive, there a chance your system fails to boot and you will have to rescue it. Backup your fstab before modifying it.

/etc/fstab:

#

# /etc/fstab

# Created by anaconda on Mon Dec 12 11:37:19 2022

#

# Accessible filesystems, by reference, are maintained under '/dev/disk/'.

# See man pages fstab(5), findfs(8), mount(8) and/or blkid(8) for more info.

#

# After editing this file, run 'systemctl daemon-reload' to update systemd

# units generated from this file.

#

/dev/mapper/rhel-root / xfs defaults 0 0

UUID=8018a50e-3c9b-47bc-a361-5a75ea898de9 /boot xfs defaults 0 0

/dev/mapper/rhel-swap none swap defaults 0 0

To get some details about the drive your want to mount, use blkid -o list.

device fs_type label mount point UUID

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

/dev/mapper/rhel-swap swap [SWAP] 4cef9cb5-a5e4-4879-a20d-f496d51b2b4c

/dev/sdb2 ext4 /home 0cb97cd5-c616-481d-845b-2cf994d77c19

/dev/sdb1 ext4 (not mounted) e8747a53-1bc1-4480-8a0f-821c464a3b9d

/dev/mapper/rhel-root xfs / 1efbf48e-14da-4b62-b021-e72369b11753

/dev/sda2 LVM2_member (in use) ZdRylK-fuHN-Z6sf-9mzt-dJRS-eE04-x9IQ4n

/dev/sda1 xfs /boot 8018a50e-3c9b-47bc-a361-5a75ea898de9

Putting these two together, add the line you want to the bottom of the list. The following line mount /dev/sdb2 to /home on boot.

UUID=0cb97cd5-c616-481d-845b-2cf994d77c19 /home ext4 defaults,noatime 0 2

When a system runs out of RAM, it allocates some processes into [SWAP] storage. This helps keep systems running smoothly, letting them take on a higher load before things start breaking. Most linux distributions come installed with SWAP storage. You can inspect this using the commands lsblk and free.

[root@localhost ~]$ lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

sda 8:0 0 25G 0 disk

├─sda1 8:1 0 1G 0 part /boot

└─sda2 8:2 0 24G 0 part

├─rhel-root 253:0 0 22G 0 lvm /

└─rhel-swap 253:1 0 2G 0 lvm [SWAP]

sdb 8:16 0 4G 0 disk

[root@localhost ~]$ free -h

total used free shared buff/cache available

Mem: 1.7Gi 797Mi 584Mi 13Mi 569Mi 973Mi

Swap: 2.0Gi 0B 2.0GiTo create and enable swap space, use the commands fdisk, mkswap and swapon. An example is shown below:

[root@localhost ~]$ fdisk /dev/sdb # use keys: n, ENTER, ENTER, w

[root@localhost ~]$ mkswap /dev/sdb1

[root@localhost ~]$ swapon /dev/sdb1

[root@localhost ~]$ free -h

total used free shared buff/cache available

Mem: 1.7Gi 797Mi 584Mi 13Mi 569Mi 973Mi

Swap: 6.0Gi 0B 6.0Gi

[root@localhost ~]$ swapon --show

NAME TYPE SIZE USED PRIO

/dev/dm-1 partition 2G 0B -2

/dev/sdb1 partition 4G 0B -3To make these changes permanent, add the swap space into fstab.

vim file

UUID=c49cdc4f-7004-4246-9c2b-ea3dd36337a3 swap swap defaults 0 0

cat file >> /etc/fstab

It is recommended to read this unit alongside unit 4. Many concepts overlap, such as creating and mounting physical file systems and logical volumes.

Red Hat may want you to mount a volume from a centralized server. To accomplish this, use NFS.

dnf install nfs-utils: if you need to install nfsmount -t nfs <ip>:/server/route /mnt: mount an nfs volume.umount /mnt: unmount nfs

To add this to your /etc/fstab/ and make it mount on boot:

echo "<ip>/server/route /mnt nfs4 defaults 1 2" >> /etc/fstabmount -a: re-load fstab, automount.

Unit 4 explains mounting at boot using /etc/fstab. Configuring network devices this way consumes additional resources and doesn't scale well. The devices can be mounted using kernel-level configuration, i.e. automount.

dnf install -y autofs: installs necessary packages and files.systemctl enable --now autofs: gets it going.systemctl restart autofs: reload config.systemctl status autofs: check how it's doing.

After installing autofs, you can now view various files beginning with /etc/auto*. /etc/auto.master holds the main configuration file. Below is an nfs config line for /etc/auto.master:

/mnt -fstype=nfs fileserver.example.com:/export/payroll

You can often omit the -fstype without breakage because the program is smart. autofs config files are also nested, so you can point your /home directory to auto.home like this:

# /etc/auto.master

/home auto.home

# /etc/auto.home

beth fileserver.example.com:/export/home/beth

joe fileserver.example.com:/export/home/joe

* fileserver.example.com:/export/home/&

You can also override configurations using the + icon. For more information look at the Red Hat Docs.

Useful if you've managed to follow the concepts in the logical volumes objective. The following two utilities resize your volumes:

lvextend: extends your logical volumes.lvextend -L20G /dev/fileserver/media:-L<size>is the new final size. So this command sets the size to 20G, it doesn't increment the current value by 20.

lvreduce: shrinks your logical volumes.lvextend -L15G /dev/fileserver/media: this shrinks the logical volume to 15G.

Similar to your /home/user directory, a group directory often acts as a home for multiple users. It is often stored in something like /home/shared/collaboration. Below are simple steps to add such a directory.

groupadd collaboration: create a new group.cat /etc/group | grep collaboration: check group exists, find GID..# collaboration:x:1013:

mkdir -p /home/shared/collaboration: create shared directory.chown nobody:collaboration /home/shared/collaboration: make the group the owner.chmod g+s /home/shared/collaboration: modify dir as group+sticky.chmod 770 /home/shared/collaboration: give rwx perms to group.useradd -G collaboration user1,user2: add some accounts to group.su user1: test it out!

To set up disk compression on a drive, you will have to wipe all data on it and start from scratch. Remove any of its entries from /etc/fstab and reformat it with fdisk.

dnf install vdo kmod-vdo: utils in case they aren't installed.vdo create --name=vdo1 --device=/dev/sdb --vdoLogicalSize=30G --writePolicy=auto: a long command to create the disk.mkfs.xfs /dev/mapper/vdo1: make file system.mount /dev/mapper/vdo1 /mnt: mount the filesystem.

Layered storage, also known as stratified storage, is basically a newer alternative to logical volumes. The system is more intuitive when it comes to features such as encryption and the storage manager, stratis-cli is fitted with powerful tools to help you with storage management.

Here are some basic stratis commands:

dnf install -y stratis-cli stratisd: install stratis packages.systemctl enable --now stratisd: enable daemon responsible for low-level storage management.stratis pool create myPool /dev/sdb /dev/sdc: create a new layered storage pool.stratis fs create myPool files: create a filesystem within your pool.mount /stratis/myPool/files /mnt: mount the filesystem as normal.lsblk: interact with pool filesystem as normal.

There are various other stratis commands: adding/removing storage, listing pools, creating encryption keys. Use man stratis <cmd> to find more info about the one you require.

During RHEL 8, stratis was introduced as a technology preview. I suppose the expectation was that it would be commonplace in later versions of RHEL but in RHEL 9, stratis is still a technology preview. It has been removed from the RHCSA 9 syllabus for the time being. To study stratis in your own time, here is their homepage.

Incorrect file permissions are either set due to generic user-group-others (ugo) permissions, or due to a misconfigured file Access Control List (ACL). Here are the reccommended steps to correct file permissions:

getfacl <file>: checks if ACLs are enabled, returns them if they are. If not enabled, either enable it or skip tochown.setfacl -m <u|g|o>:<name>:<rwx> <file>: sets facl. Omit<name>if you are setting permissions forothers. You are finished.

setfacl -m u:garry:rw script.sh: an example.

chmod <000-777> <file>: set ugo permissions using octal notation.chown <user>:<group> <file>: change the owner and/or group, hence changing permissions.

Aside: A lot of the later notes in this section were made while watching CSG on Youtube. If you find these topics confusing he will walk you through them. The notes below still help if you just want to read or if you just really need to Ctrl+F something on your exam toilet break.

A lot of system administration is based on effective scheduling. cron is a utility based on Cronos, the God of time. It allows you to create cron jobs which run a command repeatedly based on desired time constraints. Cron jobs can be interacted with using crontab.

- The syntax of cron can be found in

/etc/crontab

# For details see man 4 crontabs

# Example of job definition:

# .---------------- minute (0 - 59)

# | .------------- hour (0 - 23)

# | | .---------- day of month (1 - 31)

# | | | .------- month (1 - 12) OR jan,feb,mar,apr ...

# | | | | .---- day of week (0 - 6) (Sunday=0 or 7) OR sun,mon,tue,wed,thu,fri,sat

# | | | | |

# * * * * * user-name command to be executed

- Edit your user cron jobs using

crontab -e - View existing cron jobs using

crontab -l

A simple cron job may look like this: * * * * * echo hog >> /home/user/cronfile.txt. This job writes hog to a text file in a user's directory every minute of every day.

- Configure cron jobs for other users using the

-uflag.

Here is an example of configuring a cron job for a different user.

[root@localhost ~]$ crontab -u nginx -e

### Opens vi

1 0 1 * * cp /var/log/nginx/access.log /tmp/backup.log

## :wqRed hat linux uses systemd as its service manager. To interact with it systemctl is used.

- To enable a service to run persistently at startup, use:

systemctl enable <service>. - To start a service now, use:

systemctl start <service>. - To do these in conjunction, use

systemctl --now enable <service>. - Similarly, use the

disableandstopcommands for the opposite. - Use

systemctl status <service>to check how a service is doing.

In RHEL, systemd has various target configurations. Each target helps the system run the correct processes when that feature is used. For example graphical.target may require processes such as an X server, which basic.target does not.

- All targets are stored in

/usr/lib/systemd/system/ - The default target is stored in

/etc/systemd/system/default.target

You may have to configure the default target yourself. Here are two handy commands to achieve this:

systemctl get-default: prints default targetsystemctl set-default <name>.target: sets default target

Simple as!

There's quite a few datetime utilities across linux, below are a few key commands to help you configure time.

-

date: prints current date.man dateshows lots of configuration options.- More visual, less configurable.

-

hwclock: lower-level hardware clock.hwclock -s: sets system clock from hardware clock, useful for boot sequence.hwclock -w: sets hardware clock from system clock, less common.

-

timedatectl: in-depth time details and control panel.timedatectl set-time <date | time>timedatectl set-timezone <timezone>timedatectl set-ntp true: sets network-time-procotol; synch time to internet.

-

dnf install chrony: extra module for special NTP configuration.man chronyc && man chrony.conf: help!

A fancy Red Hat package manager. As a solo user, all you use dnf for is installing and updating packages.

dnf install <package>dnf search <package>dnf update

As a system admin, you may want to make sure all users across your network are installing the same versions of packages to minimise version conflicts.

dnf list <package>: A more sys-admin way to search, because it shows you version numbers and package groups.

[root@localhost ~]$ dnf list na* | head

Installed Packages

nano.x86_64 5.6.1-5.el9 @anaconda

nautilus.x86_64 40.2-9.el9_1 @AppStream

Available Packages

nagios.x86_64 4.4.9-2.el9 epel

navilu-fonts.noarch 1.2-19.el9 rhel-9-for-x86_64-appstream-rpmsTo find out more about where your packages come from, use the following commands:

dnf repolist all: lists all repos that come with RHEL; omitallfor enabled ones.dnf repoinfo: detailed info for enabled repos.dnf info <package>: detailed asf info about an installed package.dnf provides <file | folder>: what package made this file appear?dnf localinstall <file.rpm>: install a package directly from your computer.

To add a remote repository, you could use dnf --repofrompath but honestly, dnf is new and this command is bit confusing. Use the legacy yum command.

dnf install -y yum-utils: install theyum-config-managercommandyum-config-manager --add-repo https://your.repo.comyum-config-manager --enablerepo repo-name

Verify your repo has been added using dnf:

dnf updatednf repoinfo | less

You may want to create your own repo. To do this use createrepo

[root@localhost ~]$ dnf install -y createrepo

[root@localhost ~]$ mkdir /tmp/my_repo

[root@localhost ~]$ cp package.rpm /tmp/my_repo

[root@localhost ~]$ createrepo --database /tmp/my_repo

[root@localhost ~]$ yum-config-manager --add-repo file:///tmp/my_repo

### voila!

[root@localhost ~]$ vim /etc/yum.repos.d/tmp_my_repo.repo

### configure if needed

[root@localhost ~]$ dnf update

[root@localhost ~]$ dnf repoinfoIf you need multiple versions of the same package - like python3.6 and python3.10 - use package modules.

dnf module list: shows packages alternative modules.dnf module info --profile <module>: detailed info for listed module.dnf module install <module>: install default modulednf module install <module>:<version>/<distribution>: install specific modulednf module install nodejs:18/development

dnf module remove <module> && dnf module reset <module>: you must reset a module if you're removed it.

If you've practiced accessing the exam, you've modifier the bootloader when resetting the root password. However, the changes you make there are not permanent. To permanently edit bootloader settings, use grub2- in the cli.

grub2-editenv list: shows various settingsgrub2-get-kernel-settings: shows more settings

You may have to change some basic bootloader settings. The settings will be specified in the question but here's how to access them.

vim /etc/default/grub: open settings, make your changegrub2-mkconfig -o /boot/grub2/grub.cfg: checks for errors then places config in the boot drive.

A lot of RHCSA questions seem to relate to networking concepts. Because networking is an administrative task not often performed by most users, these questions can seem confusing. This unit will try explain basic networking concepts needed for the exam.

- Fundamentally, networks exist to allow users to share data and resources.

- Two interconnected computers form a simple network

- Using a switch, many additional devices such as printers, storage and internet gateways - all referred to as nodes - can be connected.

Each computer, or node, connected to a network has an IP address. IP addresses have two sets of variants:

-

IPv4 : Addresses which look like

192.168.10.100. -

IPv6 : Addresses which look like

fe80:badb:abe01:45bc:34ad:1313:6723:8798. -

Dynamic : Temporary addresses automatically leased from a server.

-

Static : Permanent addresses manually set by a user.

You can view current IPs assigned on a machine using ip addr.

[root@localhost ~]$ ip addr

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: enp0s3: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc fq_codel state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 08:00:27:18:c8:39 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.0.2.15/24 brd 10.0.2.255 scope global dynamic noprefixroute enp0s3

valid_lft 57620sec preferred_lft 57620sec

inet 10.0.0.10/24 scope global enp0s3

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::a00:27ff:fe18:c839/64 scope link noprefixroute

valid_lft forever preferred_lft foreverAside: IPv4 was developed when there were only a few thousand computers in the world and address combinations are limited. To get around this, networks introduced an IP address class system to seperate networks of a lower caste from wealthier ones - or to help manage usage of IPs between large and small networks. Knowledge of this is not essential, but you should be aware of it anyway.

Another IP management method introduced by network admins long ago is subnet masking. It splits up large networks into smaller ones, making them more manageable. It uses a binary AND operation to determine your subnetwork ip. Therefore, if your external ip address and subnet mask are 192.168.12.72/32, your subnet ip will be 192.168.12.64. The picture below gives some visual representaiton of how this works. Again - likely not essential - and while this may look boring, someone many years ago probably found it interesting. If you are interested, their big brains helped give us protocols such as TCP, UDP, IP and ICMP. To see some historic indie protocols, check out cat /etc/procols.

Some commands for configuring ip addresses:

-

ip: Powerful tool for general networking.ip ashows connections. -

ifconfig: Low-level networking tool. The command (without arguments) gives some good information, but always preferip. -

ifup <conn>: Activate a connection - Legacy but handy. -

ifdown <conn>: Deactivate connection -

ip link set <conn> up/down: modern approach if the above aren't available. -

nmcli con reload: yet another approach to re-starting connection. Sadly, networking is complicated.

If you are asked to create a network, you'll have to delve into the network-scripts directory.

/etc/sysconfig/network-scripts/ifcfg-enp0s8: file name structure. Replaceenp0s8with the<conn>name.- Find out more about network syntax from this red hat guide.

ifcfgfiles are persistant, and can be configued to run a selected network on boot.

A generic ifcfg file:

DEVICE=enp0s8

ONBOOT=yes

BOOTPROTO=static

IPADDR=172.10.10.110

PREFIX=24

GATEWAY=172.10.10.1

Once your connection is UP and RUNNING, you can alter complicated things such as IPv6 using nmtui.

As of RHEL 9, ifcfg is no longer the default filetype for interface configurations. By default, configurations are now stored in keyfiles which have a cleaner syntax.

This difference isn't so drastic and ifcfg will still work fine. Personally, I have learned to use ifcfg and don't want extra overhead. If you currently don't know either, consider learning about keyfiles.

A hostname helps identify a node on a network. Working in a company, you may want to change the hostname of a machine to better match where you are connecting to.

The commands used for updating hostname resolution mainly include:

hostname: prints hostname, a single line stored in/etc/hostnamehostnamectl: prints details host informationhostnamectl set-hostname <name>sets the hostname with optional,--static,--transient, or--prettyflags.hostnamectl set-hostname ""clears hostname settings

If you are still confused, here is a real-life example: connecting to a cloud computer hosted on vultr.com. The default hostname is vultr but I want to change it to my company name. An example of this is below.

[root@localhost ~]$ ssh root@company.org

# ... #

Linux vultr 5.10.0-16-amd64 #1 SMP Debian 5.10.127-2 (2022-07-23) x86_64

Last login: Thu Dec 8 15:55:08 2022 from 5.133.17.2

root@vultr:~$ hostname

# vultr

root@vultr:~$ hostnamectl

# Static hostname: vultr

# Icon name: computer-vm

# Chassis: vm

# Machine ID: af0a47bac5834e15b52bc27dad479079

# Boot ID: b796f38b2dbc4cc3a33a74ea7e460a42

# Virtualization: microsoft

# Operating System: Debian GNU/Linux 11 (bullseye)

# Kernel: Linux 5.10.0-16-amd64

# Architecture: x86-64

root@vultr:~$ hostnamectl set-hostname company.org

root@vultr:~$ exit

[root@localhost ~]$ ssh root@company.org

# ... #

root@company:~$ hostname

# copmany.orgChanges made with hostnamectl are persistent.

In terms of popular networking terminology, firewall is in the running to be star of the show. Ask any hacker on a film set what they are doing and they will explain they are disabling the firewall to access the mainframe.

Because this is red hat, we are configuring firewalls instead. The go-to tool for this is firewall-cmd. At a glance, a firewall mainly cares about zones and services. A service determines what application requires permission, and a zone determines where it goes. All zones and services can be listed with the following commands:

firewall-cmd --get-zonesfirewall-cmd --get-services

To get a better idea of services available in RHEL, visit /usr/lib/firewalld/services/. Each service contains a small .xml file giving a small description of the service, its communication protocol and ports it uses.

[root@localhost ~]$ cat /usr/lib/firewalld/services/matrix<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<service>

<short>Matrix</short>

<description>Matrix is an ambitious new ecosystem for open federated Instant Messaging and VoIP. Port 443 is the 'client' port, whereas port 8448 is the Federation port. Federation is the process by which users on different servers can participate in the same room.</description>

<include service="https"/>

<port port="8448" protocol="tcp"/>

</service>You won't need an intimate knowledge of these services for the RHCSA exam - you'll likely be told which service to enable/disable. To interact with, RHCSA will likely pick recognisable services such as http, smtp, git, etc.

You might instead be asked to create your own service. Store these in /etc/firewalld/services while using the previous directory as a template.

Some areas of a network are more trustworthy than others. Because of this, zones were developed. Zone policies are based on network trust level and source IP addresses.

- A network connection can be part of one zone at a time.

- A zone can have multiple network connections assigned to it.

- Zone configuration may include services, ports and protocols.

For each incoming packet, firewalld inspects the source IP and matches it to a zone. If no matches show up, it sends it to the default zone.

To create a new zone:

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd --new-zone extra --permanent

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd --reloadYour internet traffic is directed through interfaces in linux. You can view your interfaces with ip a.

To add an interface to a firewall zone:

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd --change-interface=enp0s1 --zone=extra --permanent

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd --reloadThere's only so many things to do with the system firewall. Below are code snippets which may help you in your exam prep. Tip: if you remember flags such as --add-, --list-, you can use bash-auto-complete to help yourself out.

- permanently add the

httpservice to the public zone

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd –-add-service=http –-zone=public –-permanent

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd --reload # load in the new change, or run the above command again without --permanent- permanently add port

80to the public zone with thetcpprocotol- each firewall port needs a protocol and the question will specify one. if not, try to guess between

tcp,udp,ipandicmp.

- each firewall port needs a protocol and the question will specify one. if not, try to guess between

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd –-add-port=80/tcp –-permanent –-zone=public

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd --reload- check your changes worked

[root@localhost ~]$ # reboot now OR firewall-cmd --reload OR systemctl restart firewalld

[root@localhost ~]$ firewall-cmd –-list-all --zone=public

public

# ...

services: cockpit dhcpv6-client http https ssh

ports: 80/tcp

protocols: # ...- check your firewall status

[root@localhost ~]$ systemctl status firewalldIf something is very wrong with the setup, you may have to temporarily disable all connections. Use firewall-cmd --panic-on to panic. This change is non-permanent, and will at most come up as an intermediary step.

A large amount of Linux security hinges of proper use of users and groups. These terms are almost self-explanatory, though for clarity:

- A group can contain multiple users.

- A user can belong to multiple groups.

- File permissions are determined by who the user is, and/or what groups they belong to.

- A file accessed by someone who isn't the main user or in their group is treated as an 'other'.

There are two files in the etc directory which contain all users and groups on the system, respectively. You can find them in /etc/passwd and /etc/group

[root@localhost ~]$ cat /etc/passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

bin:x:1:1:bin:/bin:/sbin/nologin

daemon:x:2:2:daemon:/sbin:/sbin/nologin

adm:x:3:4:adm:/var/adm:/sbin/nologin

...

[root@localhost ~]$ cat /etc/group

root:x:0:

bin:x:1:

daemon:x:2:

sys:x:3:

adm:x:4:

...The majority of these groups and users are used by the system, any added by yourself will be at the bottom.

The command to create a new user is straightfoward:

useradd matejThis will create a new entry at the bottom of the /etc/passwd file, and create a new directory named /home/matej/ to act as the user's home.

In a very similar way, create a new group using:

groupadd regularsThis will create a new entry regulars at the bottom of the /etc/group file.

To modify a user account, use the usermod command. You can do various things such as change a user's home directory, or add them to a group.

To add an existing user to an existing group:

[root@localhost ~]$ usermod -aG regulars matej

# usermod -aG <group> <user>

[root@localhost ~]$ cat /etc/group | grep regulars

regulars:x:1015:matejThe -aG flag simply means append to Groups. The user is now appended added to the end of the group in /etc/group.

Use man usermod for more granual permission information.

Similarly, you can modify groups using groupmod. While groups can have less things changed about them, you can append multiple users at once to a group or change the group name.

[root@localhost ~]$ groupmod -n new_group_name regulars

[root@localhost ~]$ groupmod -aU user1,user2 new_group_name

[root@localhost ~]$ cat /etc/group | grep new_group_name

new_group_name:x:1015:user1,user2Passwords can be changed using the passwd command. Using passwd with no arguments changes the password of the current user.

As a root user, set another user's password to expire next time they log in using the -e flag.

[root@localhost ~]$ passwd -e matejTo set a time-specific expiry and view expiry properties, use the chage command.

[root@localhost ~]$ chage -l matej

Last password change : Dec 12, 2022

Password expires : never

Password inactive : never

Account expires : never

Minimum number of days between password change : 0

Maximum number of days between password change : 99999

Number of days of warning before password expires : 7

[root@localhost ~]$ chage -M 30 matej # sets password to expire in 30 dayssudo permissions are given to the root user and any user created during system installation. New users after this are not automatically given sudo access for security reasons.

[root@localhost ~]$ useradd tom

[root@localhost ~]$ su - tom

[tom@localhost ~]$ sudo vim .

We trust you have received the usual lecture from the local System

Administrator. It usually boils down to these three things:

#1) Respect the privacy of others.

#2) Think before you type.

#3) With great power comes great responsibility.

[sudo] password for tom:

tom is not in the sudoers file. This incident will be reported.While you can add the user to the sudoers file, a neater way to do this is to use the wheel group.

[tom@localhost ~]$ exit

logout

[root@localhost ~]$ usermod -aG wheel tom # adds tom to wheel group

[root@localhost ~]$ su - tom

[tom@localhost ~]$ sudo vim .

[sudo] password for tom:

# sudo vim works!

[1]+ Stopped sudo vim .

[tom@localhost ~]$Linux has a fleshed-out security system, which can be configured based on user needs. While there is a myriad of ways to secure a system, below are the ones you need knowledge of in RHCSA.

Some firewall commands have been covered in unit 7. This unit shows other configurable settings, directly inside the firewall config.

To enable ip forwarding - a feature often used in server routing - modify /etc/sysctl.conf

[root@localhost ~]$ vim /etc/sysctl.conf

# net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

[root@localhost ~]$ sysctl -p # reload your configIf there are any firewall configurations which you are struggling to do via CLI, search firewall in gnome - remember to set the configration to permanent! man firewall-config shows help for the GUI.

By default, Linux comes with a fairly locical control system (chown, chmod) - though these often don't scale well at an enterprise level. ACLs allow for granular permission control, with multiple groups and users having different types of permissions.

getfacl <file>: Check ACL permissions of a file - check if acl is enabled.- If acl is not supported, add it after

defaultsin the drive's/etc/fstab.

- If acl is not supported, add it after

setfacl -m u:<user>:r-x <file>: sets ACL permissions, useg:for group.setfacl -R -m u:<user>:rw- <folder>: recursively sets permissions - likely what you want when applying permissions to a folder.setfacl -x u:<user>: remove ACL permisisons

If you get stuck, man setfacl for help.

Default file permissions for files are 666 (i.e. rw for all), and 777 for folders (rwx). The execute permission for folders means you can cd into them. However, all files and folders you create by default have permissions of 644 and 755 respectively. This is because the permissions are filtered through your umask before being applied to the file. You can view your umask like so:

[root@localhost ~]$ umask

# 0022The first 0 refers to the sticky bit, mainly used for collaborative projects. Visit unit 1 to refresh your knowledge of octal permissions.

umask: prints octal umask.umask -S: prints in rwx format.umask <0000-1777>: sets default umask.

The main ways default file permissions may be impacted:

- The user changes their

umaskfrom the default of 0022. - Permissions are inherited from a parent folder.

- ACLs change the default behaviour of certain files.

ssh stands for secure shell, as all traffic is encrypted. Generic ssh connections may still be vulnerable to password guessing or brute-force attacks, and can be minimsed using key-based authentication.

There are various ways to generate key-based ssh encryption keys, but a simple one is using ssh-keygen with rsa encyption. You can leave all fields blank, although setting a password is recommended.

[root@localhost ~]$ ssh-keygen -t rsa

[root@localhost ~]# ssh-keygen -t rsa

Generating public/private rsa key pair.

Enter file in which to save the key (/root/.ssh/id_rsa):

Created directory '/root/.ssh'.

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):

Enter same passphrase again:

Your identification has been saved in /root/.ssh/id_rsa

Your public key has been saved in /root/.ssh/id_rsa.pub

The key fingerprint is:

### fingerprint hereYou can then either copy your public key, .ssh/id_rsa.pub to ~/.ssh/authorized_keys in the other machine, or use the command:

ssh-copy-id -i /path/to/public/key/publickey.pub username@0.0.0.0Security-enhanced Linux is, in a way, like Windows Defender for Linux. SELinux monitors processes and checks what they do against a database of permitted events. For some RHCSE questions you may be asked to use SELinux.

getenforce- gets SELinux state.sestatus- detailed SELinux information.setenforce <enforcing | permissive | disabled>- sets SELinux state; edit/etc/selinux/configinstead to make sure the change is permanent.semanage- policy management tool for more complex use cases.

SELinux can be ran in three modes:

enforcing: prevent suspicious actions.permissive: permit suspicious actions, but log them.- permissive messages show up in

/var/log/messages- search foravc:or justselinux.

- permissive messages show up in

SELiunx applies different policies based on the origin of each file. This adds a layer of usability to protocols - for example the system or NetworkManager are allowed to do only specific things, while an unconfined user can do more.

ls -Z: view files along with their context.ps -Z: view processes along with their context.

The information printed looks a bit daunting, but it follows the pattern below:

<user>_u : <role>_r : <type>_t : <level>_intunconfined_u:system_r:NetworkManager_t:s0- More information can be found in red hat docs

All available contexts are within /etc/selinux/targeted/contexts/

To change SELinux contexts, use chcon - change context.

[root@localhost ~]$ chcon user_u:role_r:type_t:level_int file.txt

[root@localhost ~]$ ls -Z | grep file.txt

# user_u:role_r:type_t:level_int file.txtTo restore the default context, use restorecon file.txt. Use the -R flag to restore for the whole directory.

Whenever a proccess wants to use a port, SELinux will check the name of the proccess against the allowed domains and allow/block it accordingly.

SELinux comes with many common port bindings pre-defined. To list them, use semanage port -l.

semanage port -a -t <port_label> -p <tcp|udp> <port>: add port to a port label. Replace the-aflag with-dto delete the port.

A bit more info on port labeling here.

If you know what you are doing (or even if you don't), you can change SELinux to be more permissive in regard to your use-case. A lof of SELinux configuration is pre-packaged, and you simply have to turn these settings on or off.

semanage boolean -l: prints all SELinux boolean settings, with description.getsebool -a: as above, but less information to read.setsebool -P <selinux_boolean> <on | off>: sets the desired boolean. The-Pflag makes the change persistant.setsebool -P use_virtualbox on: an example.

Violations in SELiunx are sent as alerts to /var/log/audit/audit.log. This is a large file; search through it as so:

-

sealert -a /var/log/audit/audit.log- if this doesn't work, install

dnf install setroubleshoot-server

- if this doesn't work, install

-

audit2why -a: gives potential reasons for violation and how to resolve them.audit2allow -a: as above, slightly different hints.

You can begin resolving these issues using audit2why -a.

Containers are a handy way to ship software. While they were not included in the RHEL 7 or 8 specification, they are becoming increasingly promenant in industry and Red hat wants you to know some basic and intermediate commands. The three main tools for RHEL container management are podman, buildah, and skopeo.

To quickly install the appropritate tools for container management, run the command dnf module install container-tools.

For the following examples, the Docker nginx image will be used.

It may help to quickly learn the difference between these two terms. This docker-based article may help.

- An image is created when you configure a container in a specific way.

- A container is built when you run an image.

- All images are containers, and most containers are instances of an image.

In short, use podman search <image> to find all instances of the image. You can browse some registries directly, such as the Red Hat image library.

To add your own registry into the search, edit /etc/containers/registries.conf for all users or ~/.config/containers/registries.conf for the local user.

You can use podman system info to see which repositories are available to you (there's a lot of info printed from the command - it's like two-thirds down).

To actually pull the specific image, use the podman pull command.

[root@localhost ~]$ podman search nginx

### ... ###

# registry.redhat.io/3scale-amp2/apicast-gateway-rhel7 3scale API gateway (APIcast) is an OpenResty...

# docker.io/library/nginx Official build of Nginx.

# docker.io/bitnami/nginx Bitnami nginx Docker Image

# docker.io/bitnami/nginx-ingress-controller Bitnami Docker Image for NGINX Ingress Contr...

# docker.io/ubuntu/nginx Nginx, a high-performance reverse proxy & we...

# docker.io/kasmweb/nginx An Nginx image based off nginx:alpine and in...

### ... ###

[root@localhost ~]$ podman pull docker.io/ubuntu/nginx

# Trying to pull docker.io/ubuntu/nginx:latest...

# ...

# 75c20519a636dcaf79010e14e29d07bdc2b79a32eae4ad692d7d5825ec4c1302

[root@localhost ~]$ podman ps

# nothing here, image != container

[root@localhost ~]$ podman image ls

# REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

# docker.io/ubuntu/nginx latest 75c20519a636 4 weeks ago 151 MB ## image is here![root@localhost ~]$ podman rmi ubuntu/nginx # remove the image, you probably just want the default one tbh

[root@localhost ~]$ podman image ls

By default container images pre-build and abstract away complexity, but the underlying system is still there. To get a closer idea of what's happening, use the podman inspect <image> command. A fairly large JSON of information is printed, so you might want to use less or print it to a file.

[root@localhost ~]$ podman inspect ubuntu/nginx > nginx.txt

[root@localhost ~]$ less nginx.txtThere's a fair amount of information printed, but you'll likely most be interested in the "Config". It shows the exposed ports, environment varibles, and the CLI argument ran by the container.

For inspecting and generally working with images hosted on a network, use the skopeo tool. This way, you can get to understand what an image is before you download it and run it on your computer.

[root@localhost ~]$ skopeo inspect docker://docker.io/ubuntu/nginx

# {

# "Name": "docker.io/ubuntu/nginx",

# "Digest": "sha256:48df91637b19c4ca4c8b3651f43b5f05b296554be88651a3bf1a59f7fa6bf160",

# "RepoTags": [

# "1.22-22.10_beta",

# "latest"

# ],

# "Created": "2022-12-08T15:37:40.099960562Z",

# "DockerVersion": "20.10.12",

# "Labels": null,

# "Architecture": "amd64",

# "Os": "linux",

# "Layers": [

# "sha256:407b3b2e50fe8ffcb3188e03acda33d2fc306ff0105b9c4378503b29ca39569d"

# ],

# "Env": [

# "PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin",

# "TZ=UTC"

# ]

# }To quickly explain:

podman: is used for managing containers locally.skopeo: is used for managing containers online (on a network).

Most basic management techniques will use podman.

podman search nginx: search for an image in your container registry.podman pull ubuntu/nginx: download an image>.podman run nginx: finds image (locally or online) and runs it.podman run -d nginx: runs in detached mod.podman run -it nginx: runs image in interactive mode. This is not very useful for thenginximage as it requires no input from the user.podman run -d --name server nginx: runs the image with a specified name, in this case it's been named server.

podman exec <name> <command>: run a command internally within the container. Example is below.

[root@localhost ~]$ podman run -d --name server nginx

[root@localhost ~]$ curl localhost # localhost on the machine has nothing running

# curl: (7) Failed to connect to localhost port 80: Connection refused

[root@localhost ~]$ podman exec server curl localhost # inside the container there is nginx!

# <h1>Welcome to nginx!</h1>Container management:

-

podman ps: list your running containers.podman ps -a: list running and stopped containers.podman container ls: alternative syntax for the same thing.

-

podman image ls: lists all your local images. -

podman stop <name> -

podman start <name>

To stop a container you will need its name. Names are two random-ish words which you can find at the end of podman ps. Below is a generic snippet of what stopping a container may look like. To stop getting these random names assigned run your containers with a --name flag.

[root@localhost ~]$ podman run -d nginx

[root@localhost ~]$ podman run -d node # a process which is connected to nginx

[root@localhost ~]$ podman run -d node # two instances are used

[root@localhost ~]$ podman ps

# ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

# 9be7095 docker.io/library/nginx:latest nginx -g dae... 4 minutes ago Up 8 minutes ago serene_blackburn

# f257816 docker.io/library/node:latest node About a minute ago Up 5 minutes ago funny_cori

# d219251 docker.io/library/node:latest node 9 seconds ago Up 5 minutes ago hungry_chaplygin

[root@localhost ~]$ podman stop funny_cori

# funny_cori

[root@localhost ~]$ podman ps

# ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

# 9be7095 docker.io/library/nginx:latest nginx -g dae... 4 minutes ago Up 8 minutes ago serene_blackburn

# d219251 docker.io/library/node:latest node 9 seconds ago Up 5 minutes ago hungry_chaplyginSome management methods use skopeo. It is mainly a tool used to interact with remote repositories.

skopeo inspect <url>: prints online information about an image.skopeo inspect docker://docker.io/ubuntu/nginx: an example of syntax.

skopeo copy <url> <url>: copy an image over from one repository to another.man skopeo copy: for examples and extra information.

'Service' is a strong word, and in order to run a service you'll have to make a service first. The most straightforward way to accomplish this in RHEL is to write a Containerfile . When you make your own Containerfile make sure you build them as not-root.

- Config for a Dockerfile service here

Below are the commands to run the service. To see more detailed information about building this container, see the section below.

[root@localhost ~]$ ls

# myServer/

[root@localhost ~]$ podman build -t httpServer myServer/

[root@localhost ~]$ podman run -d --name server httpServer:latest

[root@localhost ~]$ podman exec server curl localhost

# <h1>My server</h1>A Containerfile is essentially an alias for a Dockerfile. An optimistic interpretation of this objective is that you simply need to understand the build command of either podman or buildah. These are the commands:

-

podman build: ⬇ -

buildah bud: ⬆ these commands are interchangeable. -

buildah bud -t httpServer myServer/: example command. It builds a container with the name-taghttpServeraccording to the Containerfile inside of themyServer/directory.

A less optimistic interpretation of 'build' is to actually write a Containerfile running a service from scratch. There are about a million ways you can write a service. Some are easier to read than others, but they can all generally get the job done. The snippet below runs a basic http service container with no network access.

This example runs on a fedora image, though Red Hat keeps mentioning their ubi: Universal Basic Image. It is basically just a more minimal RHEL distro aimed peddled by Red Hat. Find Containerfiles with ubi here, the RHEL docs. If you are serious about using containers I would recommend Alpine.

[user@localhost ~]$ mkdir myServer

[user@localhost ~]$ echo "<h1>My server</h1>" > myServer/index.html

[user@localhost ~]$ vim myServer/DockerfileFROM fedora:latest

RUN dnf -y update

RUN dnf install -y httpd

EXPOSE 80

WORKDIR /var/www/html

COPY index.html /var/www/html/index.html

CMD httpd -D FOREGROUND[root@localhost ~]$ podman build -t httpServer myServer/

[root@localhost ~]$ podman run -d --name server httpServer:latest

[root@localhost ~]$ podman exec server curl localhost

# <h1>My server</h1>This seems like a very complicated objective until you learn about a special podman command.

podman generate systemd: generates a systemd.service file based on your container. It is recommended to use all three flags below.-n: sets the name of the container you want to build.-t: sets the timeout of the service.-f: instead of printing to the screen, writes to a file.

man podman generate systemd: helps.

Copy it to /etc/systemd/system/.

Storage is already sort-of persistent in a container - it lasts until you re-build it. To actually attach a folder on your machine to the container, understand the -v flag.

podman run -v <full/local/path>:<remote/path>:Z <image>.- remember to use

:Zat the end to avoid permission errors.

- remember to use

[user@localhost ~]$ mkdir persistent

[user@localhost ~]$ touch persistent/file

[user@localhost ~]$ podman run -v /home/user/persistent:/mnt:Z nginx --name server

[user@localhost ~]$ podman exec server ls /mnt

# fileIn some scenarios you may run into SELinux problems. Consider:

- using

podmanas root. - temporarily set SELinux to permissive.

podman run --privileged=true: have podman ask for root permission.

That about wraps up the main objectives. A bit more info below if you are in a reading mood.

Containers are essentially namespaces, designed to be secure and prevent processes jumping out of a container into your host machine. Delving deep into how namespaces work on Linux can help you understand essential networking concepts. This article may be a place for you to start. A more RHEL-oriented article focusing on container basics can be found on the red-hat docs.

If you are new to containers and just trying to pass your RHCSA, don't bother with Kubernetes right now. Check it out afterwards, though.