Hello, my name is Albino Tonnina.

I’m a

senior front-end developer based in London.

I work daily with a bunch of talented people. Young developers and people who remember how to write the Box Model Hack for IE6.

Javascript aces and CSS ninjas.

Through the years I read and worked with these acronymic CSS methodologies that came out of some brilliant minds in an admirable attempt to end up **the mess, **fighting against the many specificity issues or the globally scoped nature of CSS, trying to figure out how to maintain a large codebase, the hacks etc.

frustrating job.*

I eventually realized that the level of comfortability with markup and styles can differ from developer to developer. You love it, hate it or everything in between, it may be the best or the worst part of your job. Right?

What are we trying to solve here? Here’s my list, in order of importance:

- Have a better Developer Experience.

- Work with a low-maintenance environment.

- Easy elimination of unused (dead) CSS code.

- Forget about specificity issues, hacks to cover hacks etc.

- Face the lack of the concept of local scope in CSS.

SMACSS, OOCSS, BEM, ITCSS, BEMIT, Atomic CSS? Abstract as much as you can? Get a rigid naming convention? Build the interface in reusable pieces? Let me share with you my slightly biased thoughts about these popular methodologies and finally the newcomer: Bandit.

- Separate container and content: big no to location-dependent styles.

An object should look the same no matter where you put it. You should not mimic the structure of your markup in your CSS file. - Separate skin and structure: Structure and positioning should be kept separated from visual features (color, background, border). Use extender classes to add this visual features.

OOCSS is all about abstraction and reusability. Styles are managed like Lego pieces that you mix in your markup. That should give you smaller files, reduce duplication and keep everything easy to maintain.

Also OOCSS has this nice concept of the performance freebies*: *every time you reuse something in your CSS, you’re essentially creating new styled elements with zero lines of CSS code. Sounds great.

With companies, developers come and go. This could be potentially dangerous for the stability of an architecture such as OOCSS. My fear is that it relies too much on the assumption that every developer in the company is at the same level of experience and dedication.

In the previous example, some of the styles are almost set inline (.left-pad-16), while maybe some are hidden in some CSS files located in a big ../styles/ subfolder of the project. This could lead to a bad DX if the codebase is not religiously maintained.

Dilemma: what if I really really need a .left-pad-15 class that still doesn’t exist, do I add it or I override only the styles of the tag that needs it, just this time? In my experience developers tend to do both, depending on the moment, the discipline, the hurry, how much they care.

Also, what about breakpoints and Responsive Web Design? What if that tag needs to be styled differently in a small breakpoint? It may look like this?

What about specificity now? Good luck maintaining this code.

If there are rules to break, developers will break them.

BEM may be defined as a concrete application of OOCSS. It tries to address the **naming issue **by suggesting a structured way of naming classes, based on properties.

BEM, the architecture of OOCSS with a strict set of recognizable naming rules.

This set of rules works very well. It helps to write better markup, it forces you to think in *blocks, *which is good when you want to modularize in your projects. It promotes a flat hierarchy of selectors, which is good when you have to deal with specificity issues. Also, I think that BEM it is very good when we need to prototype fast.

What I said about OOCSS applies here too.

And I’m sorry, but when I see

production code written using the BEM naming convention I don’t like to read it.

And I love to write HTML templates and SASS files! I think this is bad

readability, hence not great DX.

May I suggest also **steep learning curve?

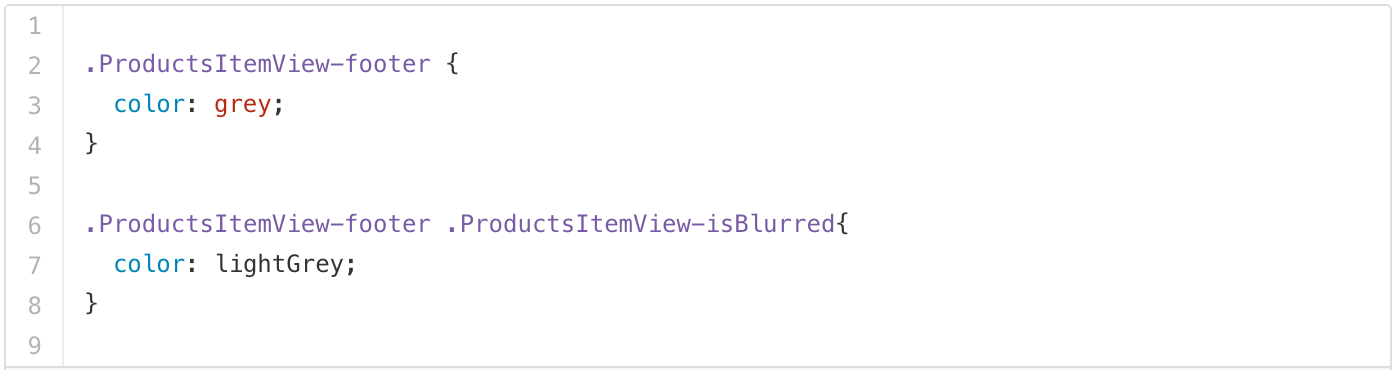

**Finally, abstracting may be hard sometimes, for example you may end up abusing

descendant selectors trying to maintain reusability:

Like OOCSS, this is a well known approach to modular CSS.

They both share

the same goal: help people write flexible and maintainable CSS.

This is the very core of SMACSS. This methodology asks developers to shift from

a *page mentality *to a pattern mentality. Pages become compositions of

modules. Think about SMACSS as a style guide, more than a rigid framework.

The categorization scheme offered by SMACSS is the following:

- Base: for defaults (html, body, etc) and resets

- Layout: for page sections

- Module: for modular reusable elements

- States: for element variations (active, inactive, pressed etc)

- Theme: color schemes, typography etc.

The purpose of this categorization: less code repetition, a more consistent experience, and easier maintenance.

- Increase the semantic value of a section of HTML and content with the new HTML5 tags: section, aside, header, *footer etc. *.

- Decrease the expectation of a specific HTML structure avoiding tag selectors.

- Difficult to qualify styles — what category? In a fast producing multi developer environment this could lead to conflicts in the codebase.

- CSS may be too detached from the markup, will we delete the classes that we don’t need anymore or we will keep bloating those theme files? The risk is to carry too much unused code around?

Here’s another approach to help us fixing **the mess **:)

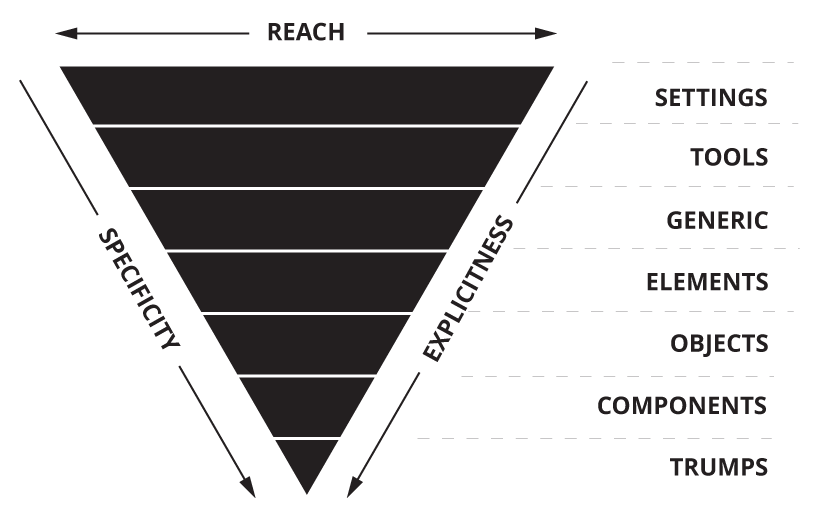

Separates CSS codebase into layers.

Similarly to SMACSS, ITCSS provides a categorization scheme for your CSS files.

From top to bottom:

- Settings: variables. Font, colors definitions, etc. No output.

- Tools: mixins and functions. No output.

- Generic: reset and/or normalize styles.

- Elements: bare HTML elements (like H1, A, etc.).

- Objects: class selectors which define undecorated design patterns, like the media object from OOCSS.

- Components: specific UI components. Majority of code.

- Trumps: utilities and helper classes with ability to override anything.

I like this methodology, I like SMACSS too. I see ITCSS sharing the same merits and faults of SMACSS.

By the way, you can mix these approaches as much as you like!

Be cautious though.

That’s all I have to say about ITCSS, I guess this article is getting a little long and I still have to start talking about Bandit :)

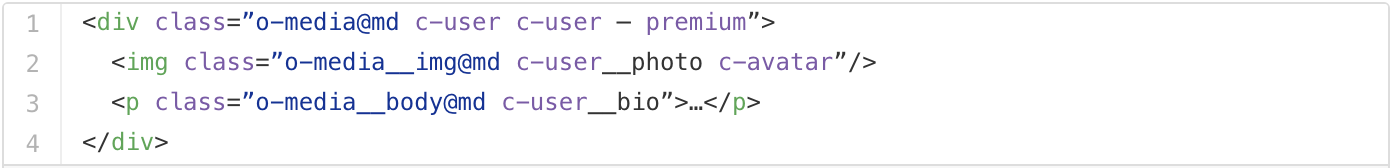

There is BEMIT that tries to address issues of BEM, like the lack of support

for RWD and the readability issues by adding categorized namespaces, like

c-

for Components, o- for Objects, u- for Utilities, and is-/has- for States.

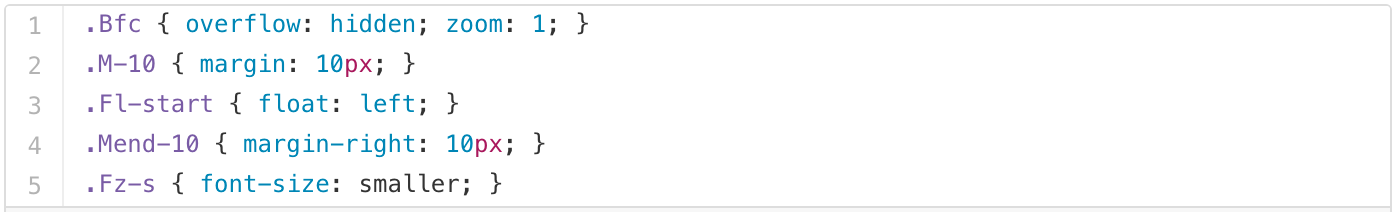

There is also another approach called Atomic Cascading Style Sheets that is all about mapping classes to a single style, like so:

Read about Atomic CSS on Smashing Magazine

Short answer is no.

I like all these approaches and yet I’m not completely happy with any of them. Over the years I sometimes found myself stuck between the apparent need to break the rules of this or that methodology opposed to the frustrating feeling of adding dirtiness to my initially clean and tidy files.

Of course, if you are working alone on a project that won’t likely evolve over time you could just choose not to worry about naming conventions, abstractions and organization of files.

On the other hand if you are working on a constantly mutating large project manipulated by many developers over time, the need of a set of principles, rules and best practices to follow is strongly needed.

application

It steals ideas from the other great methodologies.

- Have a low-maintenance environment

- Solve issues with multi developer environments

- Dead easy dead code elimination

- Have a Smooth DX, visual order, simplicity.

I’m assuming you are working with a modular application, using tools like

Backbone/Marionette/Angular/React/Ember.

Better if you manage to require

your css files together with your views at render time, there are ways to

achieve that.

All the files that create a module are contained within a folder.

Styles go

away when module goes away (dead code elimination).

Also this structure is

great if you want to load CSS asynchronously

Can work in React,

Backbone/Marionette, Ember, Angular

App/

— — modules/

— — — — -MyModule/

— — — — — — — — js/

— —

— — — — — — — -MyModule.js

— — — — — — — — styles/

— — — — — — — — — -MyModule-layout.scss

** — — — — — — — — — -MyModule-theme.scss**

— — — — — — — — templates/

— — — — — — — — — -MyModule.hbs

— —

styles/

— — — — -partials/

— — — — — — — -_base.scss

— — — — — —

— -_buttons.scss

— — — — — — — -_grid.scss

— — — — -global-styles.scss

— — — — -_variables.scss

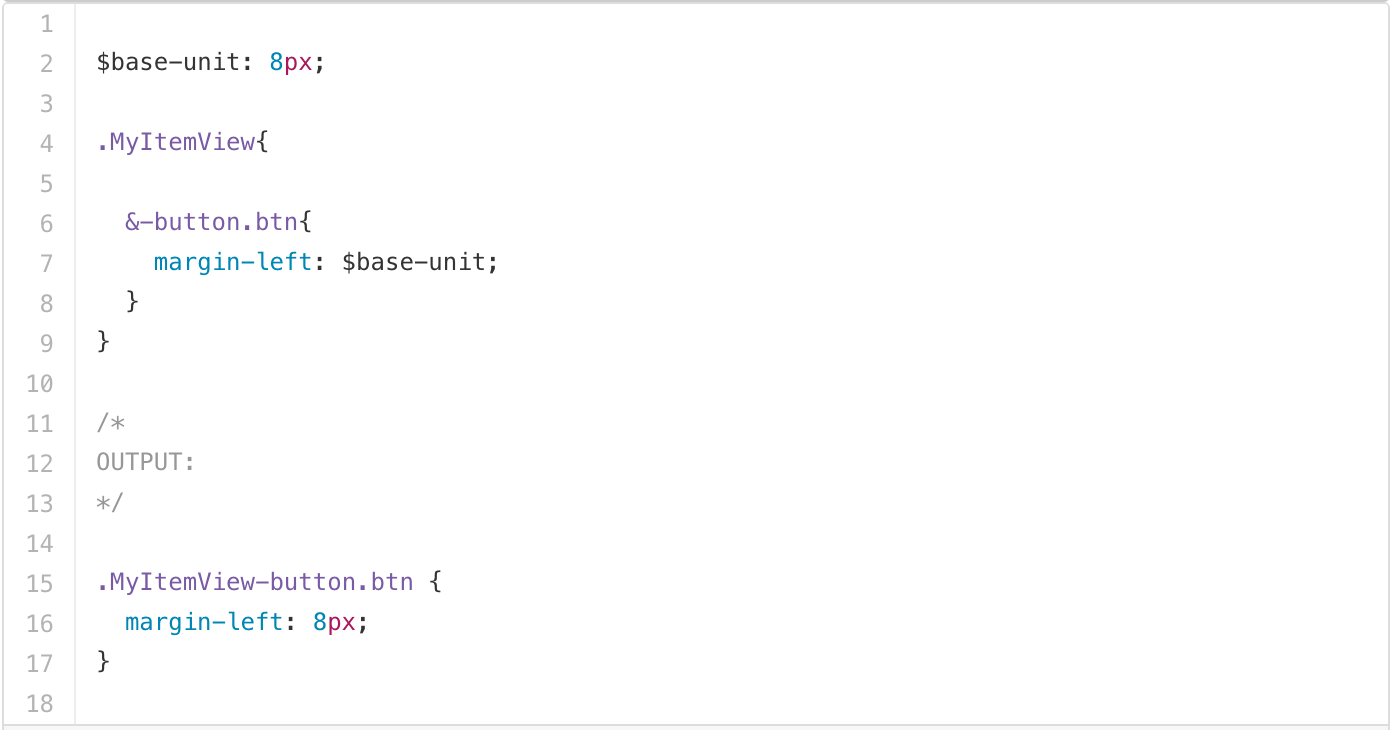

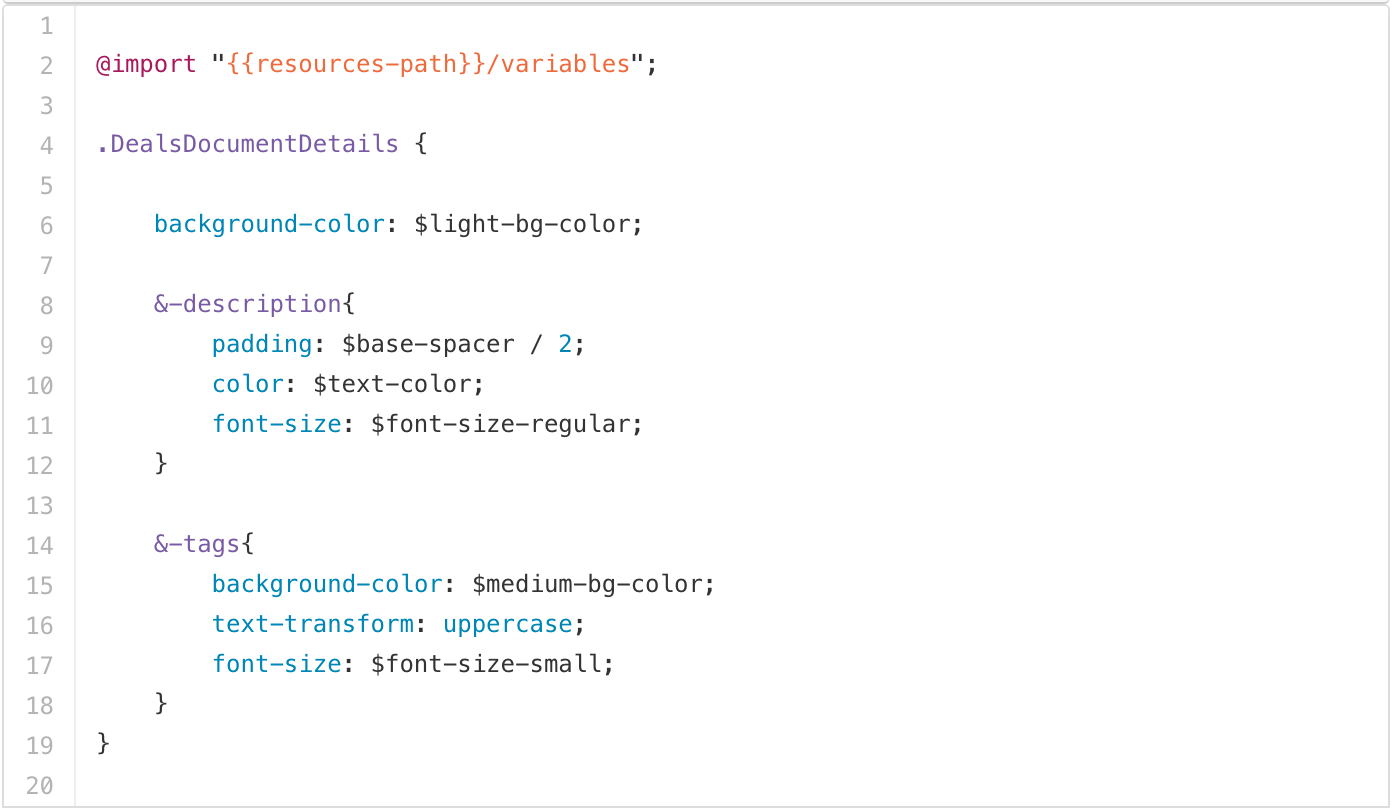

Like BEM, Bandit has a naming convention.

Only one strict rule: each

selector in a module must have the same unique prefix. It could be the

filename (if unique), it can be a composition. As long as it is unique. The rest

is up to you.

Why the unique prefix? Encapsulated styles.

Unlike OOCSS and SMACSS, let’s not abstract as much as possible, let’s isolate as much as possible.

The styles for your module are confined, they won’t affect other parts of

the application, they are kind of **specificity risk free, **so hopefully you

will deploy with a free spirit ;)

You are also quite free to invent the

naming convention of each module, everything after the first hyphen is scoped

to that module.

Or better, you can choose all together a set of conventions

that naturally fits in your project.

From BEM.

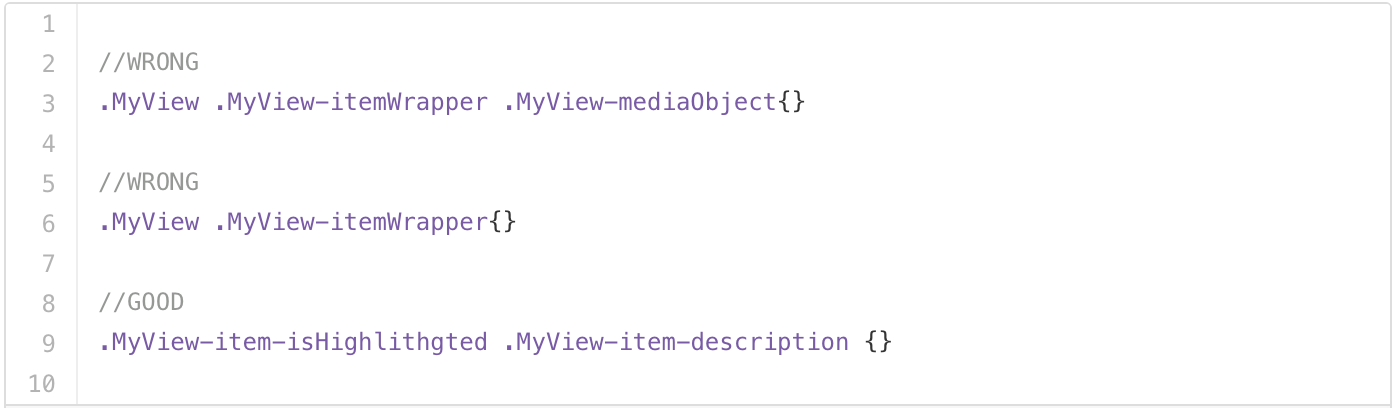

The module’s unique identifier isolates the rules so there is no need to use regularly descendant selectors to control your styles.

The benefits are quite nice. The descendant selector is the most expensive selector in CSS so the goal is to avoid it when possible.

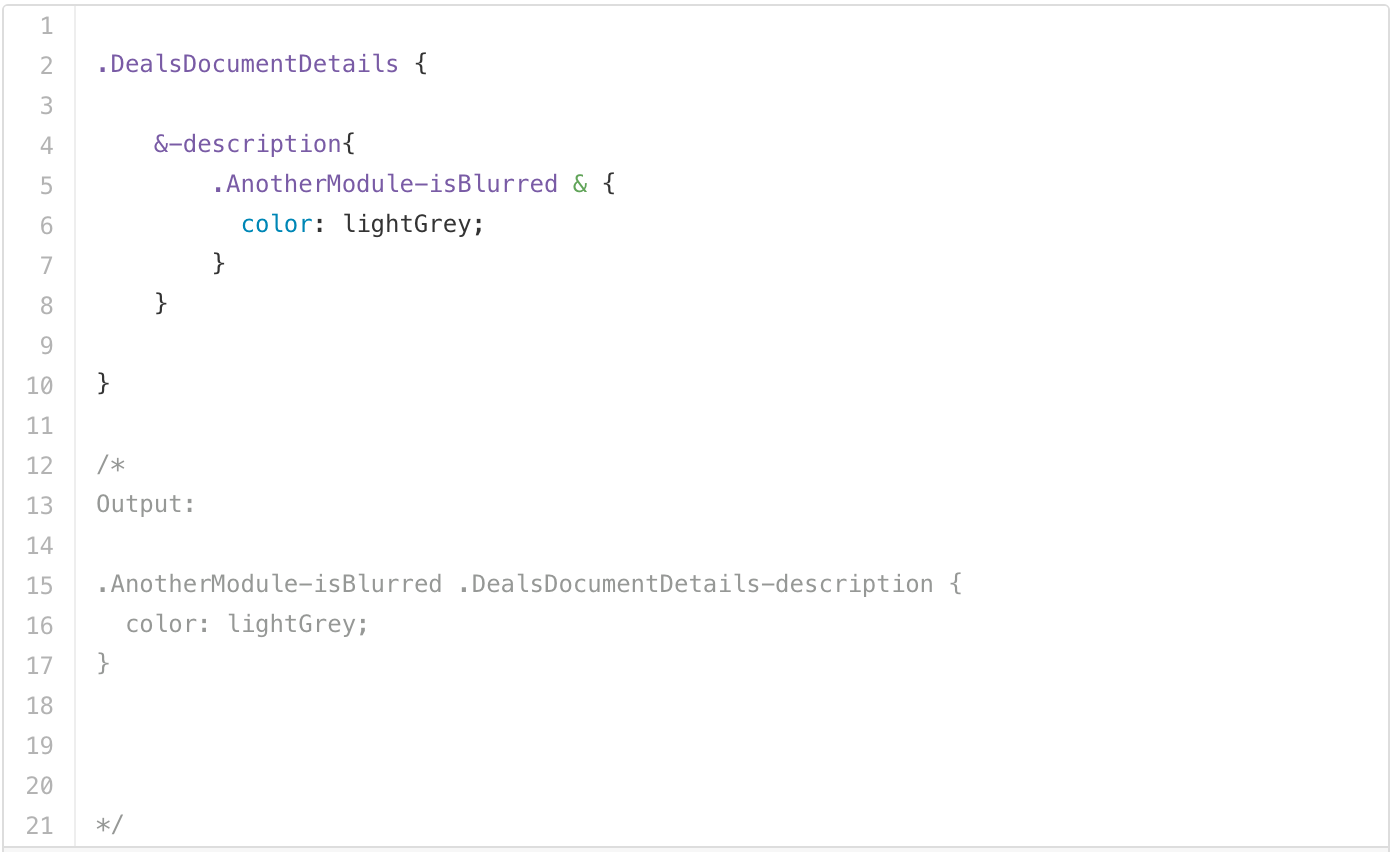

We will use descendant selectors for example when we need to override a rule of a module because of a state change:

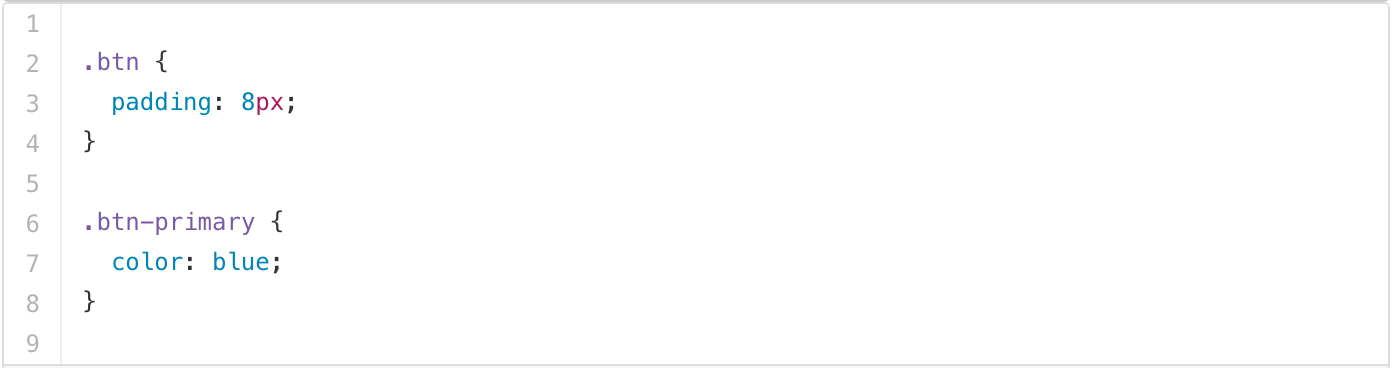

This comes from SMACSS. I think there should be a common set of classes for

basic elements or components, like Resets/Normalize styles, buttons, typography

rules, or very basic components like avatars or dropdowns.

You could use a

framework like Bootstrap or your own set of common styles.

Because of the

first principle, we isolate the code, that means more code duplication*, so we

want to have some basic styles abstracted:

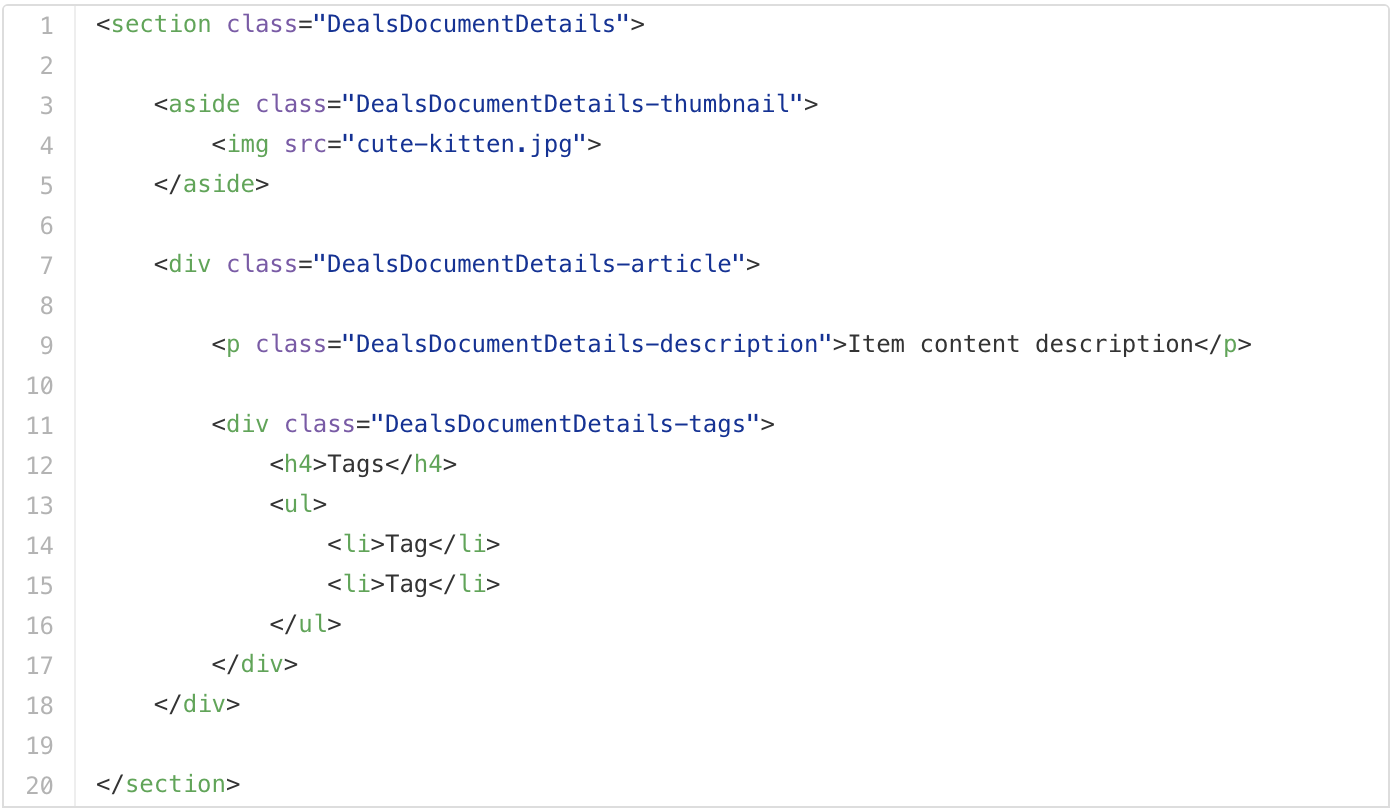

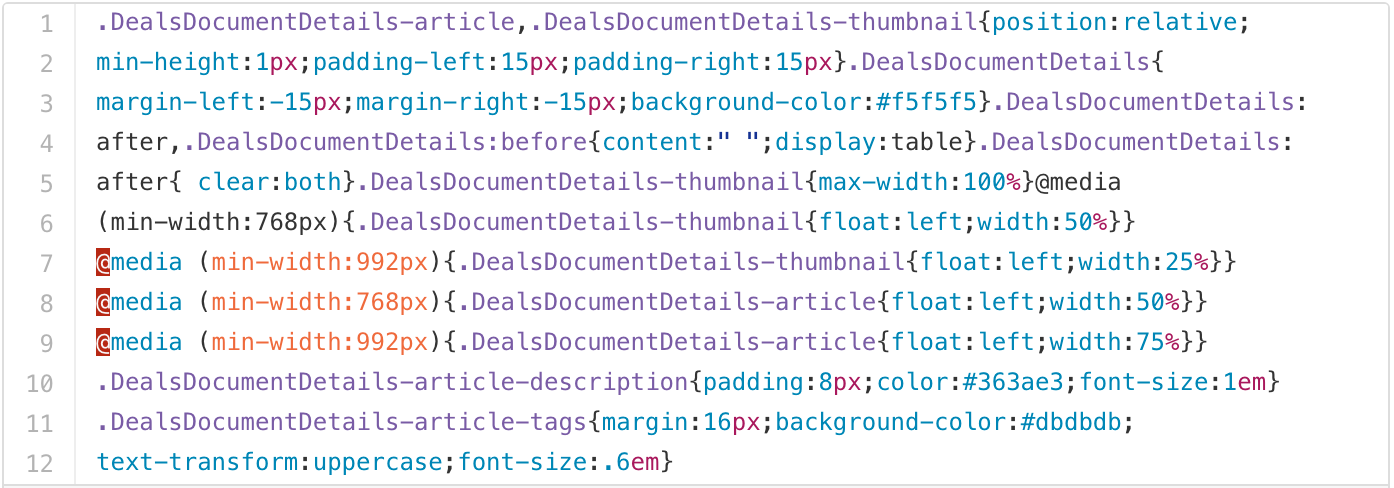

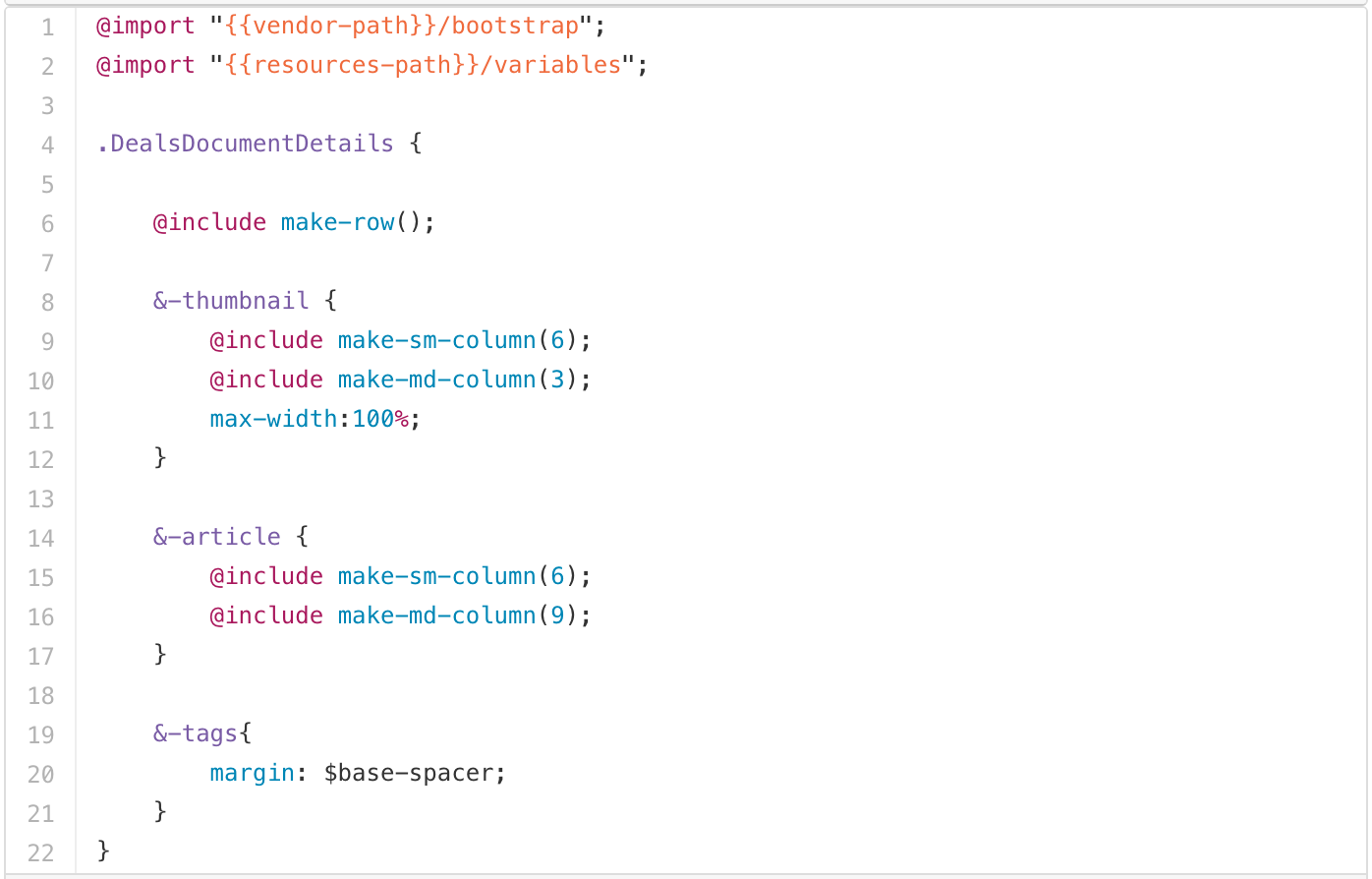

From OOCSS. Each module has two optional css files, one for the structural

styles and one for skin, like the visual features.

I call them *-layout and

-theme *files:

CSS output:

*This means duplicated code!

The output of the previous two files, compressed, is 891 bytes. That is the

size of the styles you needed for that module. If your project is composed of

100 modules we can still produce less than 100kb of CSS.

If your code

allows the injection of the module’s styles it’s even better. The code is loaded

asynchronously together with the HTML it belongs to.

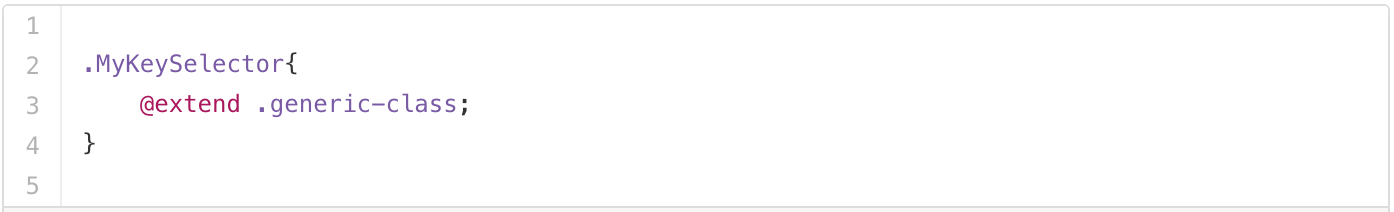

Module key selectors should never be used outside the module files.

If you need to overrides styles because of a change in a parent that you need to consider in your module you can add a *-overrides *file in your module’s style folder:

The majority of your module selectors should have low specificity: 0 0 1 0.

The specificity of an id selector is too high, it forces best avoided behaviours such as the !important declarations or inline styles to be overridden.

Two big disadvantages:

- The HTML structure is tightly coupled to the styles

- Poor performance: selectors are evaluated right to left

From SMACSS: use class names as the right-most selector

It saves little but it can add unnecessary complexity to your files. The developer has to jump around files to find the mixin definition or worse, he/she is tempted to add arguments to it, potentially breaking the old behaviour. Let your module’s CSS files be expressive: the future you or a new developer will hate you less when code changes are needed in that selector.

Unlike other methodologies, avoid class names that express sizes in your markup. They can complicate your life when you are working with breakpoints.

Use bootstrap grid mixins, do your own, but use grids.

Have mixins to manage

the structural rules, mixins to create grid elements such rows and columns for

example.

Have some, not many.

Have mixins for the grid or have a mixin to add rules

for truncating strings with ellipsis.

Even if you don’t need to. It address the problem of delivering unnecessary content.

Let autoprefixer add the vendor specific styles.

Let a postcss plugin

convert your inline assets to encoded strings.

Always use a linter like

stylelint, i.e. prevent developers to write selectors with high specificity.

There are many rules you can use to keep your code

clean and lots of useful postcss

plugins.

Bandit is more what you’d call “guidelines” than actual rules

- Captain Hector Barbossa

Selectors performance is a game to win 50ms, top.

Although:

- Don’t mess files up just because you can.

- Try to forget that !important exists.

- Write code that the next developer can understand.

- Solve your problems with dedication.