Created

May 31, 2023 09:37

-

-

Save char0n/b87e6b7809175c93f7ae6593365c32ea to your computer and use it in GitHub Desktop.

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| openapi: 3.0.0 | |

| info: | |

| title: "Multiple Examples: Core Document" | |

| description: | | |

| This document has examples for straightforward usage of `examples` in... | |

| * Parameter Object positions | |

| * Response Object positions | |

| * Request Body Object positions | |

| It includes: | |

| * cases for each JSON Schema type as an example value (except null) in each position | |

| * variously-sized `examples` objects | |

| * multi-paragraph descriptions within each example | |

| It **does not** include the following out-of-scope items: | |

| * usage of `examples` within `Parameter.content` or `Response.content` | |

| * `externalValue` (might change) | |

| It also lacks edge cases, which will be covered in the "Corner" Document: | |

| * `examples` n=1, which presents an interesting UI problem w/ the dropdown | |

| * `example` and `examples` both present | |

| * example item value that doesn't match the input type | |

| * e.g., `Parameter.type === "number"`, but `Parameter.examples.[key].value` is an object | |

| * `null` as an example value | |

| version: "1.0.2" | |

| paths: | |

| /String: | |

| post: | |

| summary: "Bonus: contains two requestBody media types" | |

| parameters: | |

| - in: query | |

| name: message | |

| required: true | |

| description: This parameter just so happens to have a one-line description. | |

| schema: | |

| type: string | |

| examples: | |

| StringExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleA' | |

| StringExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleB' | |

| requestBody: | |

| description: the wonderful payload of my request | |

| content: | |

| text/plain: | |

| schema: | |

| type: string | |

| examples: | |

| StringExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleA' | |

| StringExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleB' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: string | |

| examples: | |

| StringExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleA' | |

| StringExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleB' | |

| responses: | |

| 200: | |

| description: has two media types; the second has a third example! | |

| content: | |

| text/plain: | |

| schema: | |

| type: string | |

| examples: | |

| StringExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleA' | |

| StringExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleB' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: string | |

| examples: | |

| StringExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleA' | |

| StringExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleB' | |

| StringExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/StringExampleC' | |

| /Number: | |

| post: | |

| parameters: | |

| - in: query | |

| name: message | |

| required: true | |

| schema: | |

| type: number | |

| examples: | |

| NumberExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleA' | |

| NumberExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleB' | |

| NumberExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleC' | |

| requestBody: | |

| description: the wonderful payload of my request | |

| content: | |

| text/plain: | |

| schema: | |

| type: number | |

| examples: | |

| NumberExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleA' | |

| NumberExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleB' | |

| NumberExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleC' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: number | |

| examples: | |

| NumberExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleA' | |

| NumberExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleB' | |

| NumberExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleC' | |

| responses: | |

| 200: | |

| description: OK! | |

| content: | |

| text/plain: | |

| schema: | |

| type: number | |

| examples: | |

| NumberExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleA' | |

| NumberExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleB' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: number | |

| examples: | |

| NumberExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleA' | |

| NumberExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleB' | |

| NumberExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/NumberExampleC' | |

| /Boolean: | |

| post: | |

| parameters: | |

| - in: query | |

| name: message | |

| required: true | |

| schema: | |

| type: boolean | |

| examples: | |

| BooleanExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleA' | |

| BooleanExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleB' | |

| requestBody: | |

| description: the wonderful payload of my request | |

| content: | |

| text/plain: | |

| schema: | |

| type: boolean | |

| examples: | |

| BooleanExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleA' | |

| BooleanExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleB' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: boolean | |

| examples: | |

| BooleanExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleA' | |

| BooleanExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleB' | |

| responses: | |

| 200: | |

| description: OK! | |

| content: | |

| text/plain: | |

| schema: | |

| type: boolean | |

| examples: | |

| BooleanExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleA' | |

| BooleanExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleB' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: boolean | |

| examples: | |

| BooleanExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleA' | |

| BooleanExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/BooleanExampleB' | |

| /Array: | |

| post: | |

| parameters: | |

| - in: query | |

| name: message | |

| required: true | |

| schema: | |

| type: array | |

| items: {} # intentionally empty; don't want to assert on the items | |

| examples: | |

| ArrayExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleA' | |

| ArrayExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleB' | |

| ArrayExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleC' | |

| requestBody: | |

| description: the wonderful payload of my request | |

| content: | |

| application/json: | |

| schema: | |

| type: array | |

| items: {} # intentionally empty; don't want to assert on the items | |

| examples: | |

| ArrayExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleA' | |

| ArrayExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleB' | |

| ArrayExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleC' | |

| responses: | |

| 200: | |

| description: OK! | |

| content: | |

| application/json: | |

| schema: | |

| type: array | |

| items: {} # intentionally empty; don't want to assert on the items | |

| examples: | |

| ArrayExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleA' | |

| ArrayExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleB' | |

| ArrayExampleC: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ArrayExampleC' | |

| /Object: | |

| post: | |

| parameters: | |

| - in: query | |

| name: data | |

| required: true | |

| schema: | |

| type: object | |

| examples: | |

| ObjectExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleA' | |

| ObjectExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleB' | |

| requestBody: | |

| description: the wonderful payload of my request | |

| content: | |

| application/json: | |

| schema: | |

| type: object | |

| examples: | |

| ObjectExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleA' | |

| ObjectExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleB' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: object | |

| examples: | |

| ObjectExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleA' | |

| ObjectExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleB' | |

| responses: | |

| 200: | |

| description: OK! | |

| content: | |

| application/json: | |

| schema: | |

| type: object | |

| examples: | |

| ObjectExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleA' | |

| ObjectExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleB' | |

| text/plain+other: | |

| schema: | |

| type: object | |

| examples: | |

| ObjectExampleA: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleA' | |

| ObjectExampleB: | |

| $ref: '#/components/examples/ObjectExampleB' | |

| components: | |

| examples: | |

| StringExampleA: | |

| value: "hello world" | |

| summary: Don't just string me along... | |

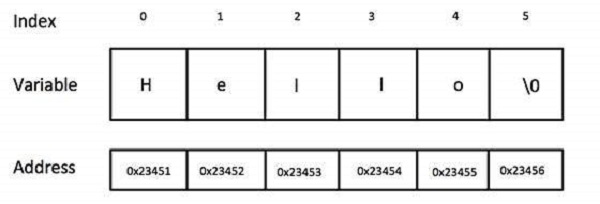

| description: | | |

| A string in C is actually a character array. As an individual character variable can store only one character, we need an array of characters to store strings. Thus, in C string is stored in an array of characters. Each character in a string occupies one location in an array. The null character ‘\0’ is put after the last character. This is done so that program can tell when the end of the string has been reached. | |

| For example, the string “Hello” is stored as follows... | |

|  | |

| Since the string contains 5 characters. it requires a character array of size 6 to store it. the last character in a string is always a NULL('\0') character. Always keep in mind that the '\0' is not included in the length if the string, so here the length of the string is 5 only. Notice above that the indexes of the string starts from 0 not one so don't confuse yourself with index and length of string. | |

| Thus, in C, a string is a one-dimensional array of characters terminated a null character. The terminating null character is important. In fact, a string not terminated by ‘\0’ is not really a string, but merely a collection of characters. | |

| StringExampleB: | |

| value: "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog" | |

| summary: "I'm a pangram!" | |

| description: | | |

| A pangram (Greek: παν γράμμα, pan gramma, "every letter") or holoalphabetic sentence is a sentence using every letter of a given alphabet at least once. Pangrams have been used to display typefaces, test equipment, and develop skills in handwriting, calligraphy, and keyboarding. | |

| The best-known English pangram is "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog". It has been used since at least the late 19th century, was utilized by Western Union to test Telex / TWX data communication equipment for accuracy and reliability, and is now used by a number of computer programs (most notably the font viewer built into Microsoft Windows) to display computer fonts. | |

| Pangrams exist in practically every alphabet-based language. An example from German is _Victor jagt zwölf Boxkämpfer quer über den großen Sylter Deich_, which contains all letters, including every umlaut (ä, ö, ü) plus the ß. It has been used since before 1800. | |

| In a sense, the pangram is the opposite of the lipogram, in which the aim is to omit one or more letters. | |

| A perfect pangram contains every letter of the alphabet only once and | |

| can be considered an anagram of the alphabet. The only perfect pangrams | |

| that are known either use abbreviations, such as "Mr Jock, TV quiz PhD, | |

| bags few lynx", or use words so obscure that the phrase is hard to | |

| understand, such as "Cwm fjord bank glyphs vext quiz", where cwm is a | |

| loan word from the Welsh language meaning a steep-sided valley, and vext | |

| is an uncommon way to spell vexed. | |

| StringExampleC: | |

| value: "JavaScript rules" | |

| summary: "A third example, for use in special places..." | |

| NumberExampleA: | |

| value: 7710263025 | |

| summary: "World population" | |

| description: | | |

| In demographics, the world population is the total number of humans currently living, and was estimated to have reached 7.7 billion people as of April 2019. It took over 200,000 years of human history for the world's population to reach 1 billion; and only 200 years more to reach 7 billion. | |

| World population has experienced continuous growth since the end of the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the Black Death in 1350, when it was near 370 million. The highest population growth rates – global population increases above 1.8% per year – occurred between 1955 and 1975, peaking to 2.1% between 1965 and 1970. The growth rate has declined to 1.2% between 2010 and 2015 and is projected to decline further in the course of the 21st century. However, the global population is still growing and is projected to reach about 10 billion in 2050 and more than 11 billion in 2100. | |

| Total annual births were highest in the late 1980s at about 139 million, and as of 2011 were expected to remain essentially constant at a level of 135 million, while deaths numbered 56 million per year and were expected to increase to 80 million per year by 2040. The median age of the world's population was estimated to be 30.4 years in 2018. | |

| NumberExampleB: | |

| value: 9007199254740991 | |

| summary: "Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER" | |

| description: | | |

| The `MAX_SAFE_INTEGER` constant has a value of `9007199254740991` (9,007,199,254,740,991 or ~9 quadrillion). The reasoning behind that number is that JavaScript uses double-precision floating-point format numbers as specified in IEEE 754 and can only safely represent numbers between `-(2^53 - 1)` and `2^53 - 1`. | |

| Safe in this context refers to the ability to represent integers exactly and to correctly compare them. For example, `Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 1 === Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 2` will evaluate to `true`, which is mathematically incorrect. See `Number.isSafeInteger()` for more information. | |

| Because `MAX_SAFE_INTEGER` is a static property of `Number`, you always use it as `Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER`, rather than as a property of a `Number` object you created. | |

| NumberExampleC: | |

| # `description` and `summary` intentionally omitted | |

| value: 0 | |

| BooleanExampleA: | |

| value: true | |

| summary: The truth will set you free | |

| description: | | |

| In some programming languages, any expression can be evaluated in a context that expects a Boolean data type. Typically (though this varies by programming language) expressions like the number zero, the empty string, empty lists, and null evaluate to false, and strings with content (like "abc"), other numbers, and objects evaluate to true. Sometimes these classes of expressions are called "truthy" and "falsey". | |

| BooleanExampleB: | |

| # `description` intentionally omitted | |

| value: false | |

| summary: Friends don't lie to friends | |

| ArrayExampleA: | |

| value: [a, b, c] | |

| summary: A lowly array of strings | |

| description: | | |

| In computer science, a list or sequence is an abstract data type that represents a countable number of ordered values, where the same value may occur more than once. An instance of a list is a computer representation of the mathematical concept of a finite sequence; the (potentially) infinite analog of a list is a stream.[1]:§3.5 Lists are a basic example of containers, as they contain other values. If the same value occurs multiple times, each occurrence is considered a distinct item. | |

| ArrayExampleB: | |

| value: [1, 2, 3, 4] | |

| summary: A lowly array of numbers | |

| description: | | |

| Many programming languages provide support for list data types, and have special syntax and semantics for lists and list operations. A list can often be constructed by writing the items in sequence, separated by commas, semicolons, and/or spaces, within a pair of delimiters such as parentheses '()', brackets '[]', braces '{}', or angle brackets '<>'. Some languages may allow list types to be indexed or sliced like array types, in which case the data type is more accurately described as an array. In object-oriented programming languages, lists are usually provided as instances of subclasses of a generic "list" class, and traversed via separate iterators. List data types are often implemented using array data structures or linked lists of some sort, but other data structures may be more appropriate for some applications. In some contexts, such as in Lisp programming, the term list may refer specifically to a linked list rather than an array. | |

| In type theory and functional programming, abstract lists are usually defined inductively by two operations: nil that yields the empty list, and cons, which adds an item at the beginning of a list. | |

| ArrayExampleC: | |

| # `summary` intentionally omitted | |

| value: [] | |

| description: An empty array value should clear the current value | |

| ObjectExampleA: | |

| value: | |

| firstName: Kyle | |

| lastName: Shockey | |

| email: kyle.shockey@smartbear.com | |

| summary: A user's contact info | |

| description: Who is this guy, anyways? | |

| ObjectExampleB: | |

| value: | |

| name: Abbey | |

| type: kitten | |

| color: calico | |

| gender: female | |

| age: 11 weeks | |

| summary: A wonderful kitten's info | |

| description: | | |

| Today’s domestic cats are physically very similar to their wild | |

| ancestors. “Domestic cats and wildcats share a majority of their | |

| characteristics,” Lyons says, but there are a few key differences: | |

| wildcats were and are typically larger than their domestic kin, with | |

| brown, tabby-like fur. “Wildcats have to have camouflage that’s going to | |

| keep them very inconspicuous in the wild,” Lyons says. “So you can’t | |

| have cats with orange and white running around—they’re going to be | |

| snatched up by their predators.” As cats were domesticated, they began | |

| to be selected and bred for more interesting colorations, thus giving us | |

| today’s range of beautiful cat breeds. |

Sign up for free

to join this conversation on GitHub.

Already have an account?

Sign in to comment