The Caretaker's Everywhere at the End of Time music project is a six-album series which explores dementia and memory loss by looping and degrading samples of ballroom music from the ~1920s–1940s. The Caretaker describes Stage 1 as "most like a beautiful daydream. The glory of old age and recollection. The last of the great days." Andrew Hess's Everywhere at the End of Time aims to produce a Line Rider track series set to The Caretaker's project, with this month's Stage 1 release looping various scenes from America around the 1950s. During that decade (and I will return to these topics):

- Grassroots direct actions were being organized by the civil rights movement in response to Northern and Southern white resistance against the Supreme Court's 1954 ruling on Brown v. Board of Education.

- The country's rising automobile industry, fueled by increasing car ownership, grew to become a major pillar of US economic power and the hegemonic mode of personal mobility.

- The country was being geographically and economically transformed by the Interstate Highway System created by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which was used as pretext to destroy working-class and nonwhite urban neighborhoods to build large freeways from the suburbs which in turn accelerated migration of white people from racially mixed cities to segregated suburbs.

- The Cold War created anxieties about nuclear annihilation, communist subversion at home, leftist decolonization abroad - with the Korean War (1950–1953) being a notable exception to the US's typical foreign intervention strategy of relying on CIA operations to overthrow governments and install US-friendly dictatorships - and Soviet technological superiority with the 1957 launch of Sputnik.

Hess's EATEOT Stage 1 presents nostalgic scenes of middle-class leisure, courtship, and mobility from this period of US history:

Figure 1: Stills from Andrew Hess's EATEOT Stage 1. 1) Car with 1950s-style tailfins, probably a Chevrolet Bel Air (late 1950s), and implied to be the vehicle used for transportation by the rememberer of the memories in the track; 2) Nighttime picnic with two glasses of wine; 3) Diner with two straws sticking out of a milkshake at a window; 4) Marquee listing "Vertigo" (1958 film) as the currently-screening movie at a theater with off-screen promotional posters of "Gone with the Wind" (1939), "Attack of the 50 Foot Woman" (1958), "Vertigo" (1958), and "Forbidden Planet" (1956) on the wall.

My not-quite-first reaction while watching Hess's EATEOT Stage 1 was:

This is because of the music accompanying EATEOT Stage 1 and the "Married Life" montage, as well as the visual similarities with "Married Life" scenes which I remember clearly:

Figure 2: Juxtaposed stills from Pixar's Up and Andrew Hess's EATEOT Stage 1. 1 & 2) The striking similarities between the Carl and Ellie's house in Up's "Married Life" montage (left) and the house at the start of EATEOT Stage 1 (right) - right down to the shingles and window casings and gate of the white picket fence - reflect Hess's modeling of the house in EATEOT Stage 1 after the house from Up. 3 & 4) The similarities between Carl and Ellie climbing a hill in Up's "Married Life" montage (left) and Bosh riding up hills in Hess's EATEOT Stage 1 (middle & right) are probably coincidental, but the latter still reminded me of the former.

Then I rewatched the montage and realized to my horror that after watching (or as a result of watching?) EATEOT Stage 1, whose nostalgic memories match the tone of the first quarter of "Married Life", those were the only scenes of "Married Life" whose visual content I could immediately recall. I had somehow lost my visual memories of the montage's subsequent scenes of grief and regret and gaman. As Victoria Chang writes in Dear Memory:

We often speak of memory as something that lingers, that returns again and again. Maybe memory is more like a homicide, each time it returns, it's a new memory, one that has murdered all the memories before.

Those scenes I had forgotten are the parts which had made Up so meaningful and moving when I watched it as a lonely and isolated and depressed gay Chinese American kid going through high school in suburban Metro Detroit around the start of the 2010s. In the shadow of California's passing of Prop 8 and the automotive industry crisis of 2008-2010 which was economically pummeling Metro Detroit, I was aching for the promise of a white picket fence and a white husband and a white homonormative lifestyle offered by the same-sex marriage campaign talking points (almost explicitly, such as in this Australian TV ad) and the It Gets Better videos (much more implicitly) and the first quarter of "Married Life" (by projection) - a promise which was both nearly the only remaining reason I could find to keep living at the time and the thing which had seemed most unattainable to me based on what I had seen of how white gay men talked about asians online and in media. But there was no alternative on offer, so what could I do? Hence my willful and depressive retreat into aching daydreams for this american life without such unruly things as nonwhite bodies in a white society. Without such unsightly things as me. And yet -

And yet knowing that the [Gay] American Dream is really just a beautiful daydream - and that beauty is in the eye of the beholder - doesn't make the escapism of its hollow promises less tempting. Indeed, the parts of Up which I've remembered with visual detail and not just as summarized plot points are those idealized frames showing the life I wished I could be able to have: that confidently respectable 1950s-esque heteronormative white domesticity which I was told to desire and aspire to, except maybe with a same-sex marriage. If given the opportunity I'd certainly be tempted to try it on like a Disney ride or Halloween costume, to cosplay as someone who could've shared in that post-WWII optimism rather than inheriting their mother's traumas of growing up in Taiwan under the political repression of the CIA-supported White Terror period (1949–1992). How nice it would be to become Carl or Ellie in Up - either will do / they all look the same anyways / I'll even settle for being the miscarried fetus or the talking dog / anyone but Russell / just press the damn button and turn me white already / I'm so tired from being paranoid about any interaction I have with white strangers. If I could just sink into the numb bliss of historical amnesia, even just for a moment, or two moments, or three moments, or...

Nearly a thousand [steelworkers at Great Lakes Works] have since lost their jobs. The layoffs came at an inauspicious time for Donald Trump, who won the Presidency, in 2016, by flipping Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania by a combined total of seventy-seven thousand votes. (His winning margin in Michigan, barely ten thousand votes, was the slimmest of any state.) Two days before Election Day, Trump had held a rally in Macomb County, Michigan, a national bellwether for the white working-class voters who were once known as Reagan Democrats. “We are going to stop the jobs from going to Mexico and China and all over the world,” Trump said. “We will make Michigan into the manufacturing hub of the world once again.” A Republican Presidential candidate had not won Macomb County since 2004; Trump carried it by nearly fifty thousand votes.

(source)

Throughout most of the 1950s, the big three automakers mostly earned hefty profits—but autoworkers themselves suffered from layoffs and insecurity beneath those numbers. [...] The auto industry’s instability started in the immediate aftermath of World War II, when materials shortages bedeviled the business. [...] With thousands of parts going into each car, any missing items—from seat frames to bolts and screws—could quickly result in tens of thousands of auto layoffs in Detroit. [...]

Consider how workers fared in 1950, which was generally a good year for the auto industry, with aggregate production and sales setting new records. But when the Korean War began in June, the business took a severe hit. Unlike during World War II, when Detroit became known as “the arsenal of democracy,” defense spending during the Korean War spread throughout the country to places like New Jersey, Ohio, Missouri, and California—while metals rationing strictly limited the number of cars that could be built in Detroit.

Prospective workers, however, streamed into Detroit from around the country because they heard only about industry profits, never about the problems. As a result, unemployment in Detroit was rarely under 100,000 people throughout the Korea conflict. Sometimes it reached as high as 250,000 job seekers, heavily concentrated among autoworkers.

(source)

...or you get in trouble when beautiful daydream ossifies into compulsive lie, when the escapism of amnesia takes over your life, when your nostalgia directs you away from any future which would meet everyone's basic social, material, and psychological needs for a dignified life. When your politics are paralyzed because you've trapped yourself in a fictitious past of the great days.

And so we return to EATEOT Stage 1, which revisits a similar flavor of nostalgia as that exploited by the 2016 Trump campaign, instead presenting it through groundhog-day loops of amnesic memory which trap the rememberer in an idealized version of the 1950s. The sense of trappedness comes from the way EATEOT Stage 1 constructs and repeats its memories. Each memory in EATEOT Stage 1 works to maintain spatial continuity between its beginning and end, bending the structure of space so that the rememberer/viewer can continue from the end back through the start as smoothly as possible, so that they might keep looping the memory over and over without noticing.

Figure 3: Stills from Andrew Hess's EATEOT Stage 1. 1-3) The frames at the starts of the A3, A6, and B5 memories; 4-6) The frames at the ends of the A3, A6, and B5 memories. Note that the A3 memory depicts a river which flows down a waterfall into itself.

But the boundaries of each memory attempt to create this flow only for it to be ruptured by hard cuts between successive repeats of that memory. Each cut is a discontinuity, a flow-killer, a scar in time and space. It points out the uncanny structure of the memory, reminding you that you're in a loop with no exit, a loop which was designed to smoothly enclose you but which has not quite fulfilled its purpose. It might be nice to get lost in your happy memories and lose track of time, but you're pulled back and suspended instead in only a partial sense of immersion. The hard cuts disrupt the hypnotic aim of the nostalgic memories. This conflict within the structure of EATEOT Stage 1 creates the sensation of being trapped.

I became more and more aware of this trapped feeling as I noticed what my tiger-parented and internet-pilled mind, always desperate for novel stimuli and always anxious in the background about being caught "wasting" time, would start to do after several iterations of each memory: I would try to maintain attention by scanning for scenery details I hadn't noticed (as if I were playing "I Spy" during an interminable road trip), I would intellectualize by analyzing what I was seeing in order to avoid facing the emotions I was feeling, I would start to multitask by writing notes without pausing the track, I would compulsively switch to other windows and switch back after half a second, and so on. All of these are strategies my mind has honed to cope with feeling locked out from its drive to make new memories - and this was an experience of trappedness rather than boredom, because I wanted to go back and rewatch the track.

The great sonic-theoretical contribution of The Caretaker to the discourse of hauntology was his understanding that the nostalgia mode has to do not with memories but with a memory disorder. The Caretaker's early releases seemed to be about the honeyed appeal of a lost past [...]

As The Caretaker project has developed, though, it has become more about amnesia than memory. Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia is not about the inability to remember, so much as the incapacity to make new memories. The inability to distinguish the present from the past. The cultural pathology of a clipshow culture locked into endless rewind.

(from the blog of cultural theorist Mark Fisher, a collaborator of The Caretaker)

As I kept rewatching EATEOT Stage 1, I found myself engaging with the track differently - I would instead start jumping back and forth between different memories after a few repeats of each one, or hover over the YouTube playback preview thumbnails for the track, or my mind would wander for a few minutes and then I'd replay that segment of the track from the start, or I'd watch every repeat of various memories with the specific purpose of understanding my emotional experiences of them for this review. I think all of these behaviors are attempts for me as a viewer to engage with these memories on my own terms, in a random-access mode where I wouldn't have to experience being trapped again while engaging with all of the many things I find fascinating about the contents of the memories in EATEOT Stage 1.

What sticks out to me about the contents of the memories is the effect they have on the nostalgia depicted in EATEOT Stage 1. There are many things I could discuss, such as the way the track mixes disparate (and incompatible) drawing projections for different objects - even in the same frame - or the way it reuses some drawings from other works (such as the house from Pixar's Up and the conifers from Andrew Hess's previous tracks The Wild and Where the Grass is Green) and repeats other drawings across memories in EATEOT Stage 1 as if to turn them into symbols abstracted from reality. For this review I will focus on the omissions - the things left out which haunt the track by their exclusion.

Many memories in EATEOT Stage 1 seem to involve other people, yet no other living person is shown in the track - in fact, the only other animals depicted by the track are a seagull and some marine invertebrates on a beach, and the only other humans are characters on movie posters. The memories imply a romantic interest who is noticeably absent. The chaotic vibrancy of city life has evaporated, replaced by empty streets under the grids of windows in urban canyons and the distant silhouettes of towers. Even traffic has disappeared, and the few drawings of cars are all well outside the city. I imagine these omissions were also/primarily motivated by other artistic reasons, and/but they create an undertone of loneliness to the memories, as if the rememberer were the only real person left in their mental world. They are condemned to relive the happy times, but without any of the people who had made that world rich and meaningful, who had given emotional substance to those memories.

Figure 4: Various scenes from EATEOT Stage 1, fixed in time and devoid of life. 1) Bosh's splash of water from entering a swimming hole is eternally frozen in memory. 2) An empty rowboat in a river somehow has its oars held in place by...nobody. 3) Bosh crosses a four-lane highway or road with no cars on it. 4) The only other human beings shown in EATEOT Stage 1 are shown in movie posters (note the cars and the freeway in the poster for Attack of the 50 Foot Woman). 5) No other person is ever seen on the residential street in a city. 6) No other sign of human presence is ever seen in the big city, either. 7) A lake with an empty boat and abandoned beach toys (note also the strange combination of orthographic projection for the boat and flat projection for the picnic bench). 8) No farmer can be seen on the tractor, nor can any farm animal be seen in the surrounding farm despite the depiction of a barn. 9) The trolley indicates a San Francisco even more empty of people than it was in the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The sum effect of the reused symbols and absences on EATEOT Stage 1 is to make its depicted nostalgia feel hollowed-out and estranged - the memories are LaCroix-ified echoes of the real experiences, compressed down to the point of losing the humanity enabled by social existence. And by depicting the 1950s and cars and depopulated cities and an alienated experience of [past] life, EATEOT Stage 1 also draws an accidental connection to the racially-driven patterns of white flight from cities to suburbs accelerated by the rise of automobiles and highways in the 1950s. This brings me to the back to the topic of nostalgia, race, and racism.

In fact, the first reaction I had while watching the first memory of EATEOT Stage 1 was "oh wow this looks like how I imagine a small town in the 1950s to have been like. I wonder what it might've felt like to be a Japanese American in this kind of place right after the war, so soon after the violence of being forced out of your home into the US-run concentration camp where you were trapped for half your childhood, to be released only with $25 and a one-way train ticket after so much was taken from you, to be surrounded by white people who were fine with what your country did to you - or maybe even still wanted you gone". In other words, for me this track is filled with ghosts from the 1945–1955 decade of Asian & Asian American history.

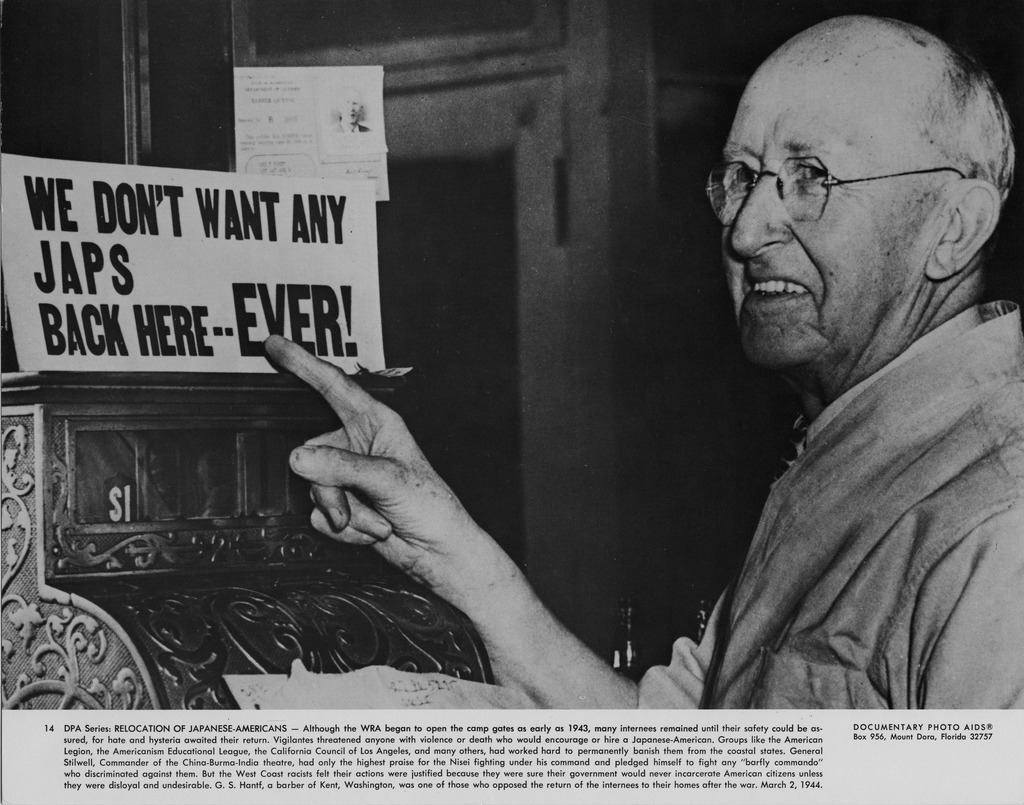

Figure 5: Barbershops. 1) Barber G.S. Hantf of Kent, Washington (population ~3000 at the time), points to his sign which says "We don't want any Japs back here...EVER!". From March 1944, after Japanese Americans were allowed leave the camps. (source) 2) Still from Andrew Hess's EATEOT Stage 1, showing a barbershop in a small rural town with a big "WELCOME" painted on the side of its building.

The Nisei faced additional psychological challenges during their resettlement after the war. Many struggled with the fact that they had been powerless to resist the injustice perpetrated upon them and wondered if somehow they, or Japanese Americans as a group, were responsible for their treatment. Although post-incarceration responses among the Nisei varied, virtually all avoided discussing their wartime experience. The detachment and avoidance of trauma-related stimuli demonstrated by the Nisei have been seen as paralleling symptoms of posttraumatic stress. However, Tetsuden Kashima referred to avoidance of discussion about the camps as a form of "social amnesia" that reflected not individual psychopathology, but rather a group attempt to suppress unpleasant memories and feelings.

[...] the Nisei maintained a low profile to avoid calling negative attention to themselves and focused instead on fitting into American culture. Mass likened their response to an abused child who hopes that by acting correctly he will be accepted: "By trying to prove we were 110 percent American, we hoped to be accepted." The attempts of the Nisei to suppress their incarceration memories, blend in, and "prove" themselves to the country that had imprisoned them, however, took a psychological toll. Although precise data are not available, Mass also observed that a prevalence psychosomatic disorders, peptic ulcers, and depression in the Nisei population, conditions that she considered to be negative effects of the psychological defenses they adopted.

The Niseis' postwar responses to the incarceration also had important intergenerational impacts for their Sansei children, the majority of whom were born after the war had ended. While the Sansei grew up hearing their parents refer to "camp" in indirect and cryptic ways (often as a reference point in time using phrases such as "before camp" and "after camp"), they experienced their parents' reluctance to fully discuss their incarceration experiences and sensed that what had happened was too painful to discuss. The extended silence created a gap in the Sansei's own personal history and identity development, and many carried feelings of sadness and anger about their parents' unspoken pain. The Sansei were also affected by the Niseis' efforts to blend into mainstream America and protect their children by minimizing the transmission of Japanese culture and language.

(source)

There is social amnesia as a collective condition of an abused people attempting to cope with the violence done to them; for Japanese Americans, this ended up being an incomplete process as they found themselves still haunted by their experiences. Then there is social amnesia as the collective condition of the abuser society unwilling to face the racist violence they've done to others. Given the amount of history made during the 1950s regarding racism and desegregation - with Rosa Parks and the 1955–1956 Montgomery bus boycott among the more widely-taught examples - how are we to understand the omission of even any minimal hint of such history from the nostalgia for that decade in EATEOT Stage 1? Why is the popular nostalgia directed at that period's middle-class white suburban experience (segregated, though scrubbed of the mechanisms built to maintain that segregation), rather than the disruptive power ordinary people exercised in fighting together to bend history towards justice (a sense of futurity which feels so distant in our current moment dominated by climate change and capitalist realism and pandemic anti-solidarity)? What would it mean if the misremembering at the heart of the nostalgia about the 1950s as the great days were to disintegrate, as we might expect it to in the later stages of a six-stage project about dementia? And who is doing this misremembering? What happens to them and the ghosts haunting them as they fade out of existence? What will fill the void created by their demise?

I bring up Korea to collapse the proximity between here and there. Or as activists used to say, “I am here because you were there.”

I am here because you vivisected my ancestral country in two. In 1945, two fumbling mid-ranking American officers who knew nothing about the country used a National Geographic map as reference to arbitrarily cut a border to make North and South Korea, a division that eventually separated millions of families, including my own grandmother from her family. Later, under the flag of liberation, the United States dropped more bombs and napalm in our tiny country than during the entire Pacific campaign against Japan during World War II. A fascinating little-known fact about the Korean War is that an American surgeon, David Ralph Millard, stationed there to treat burn victims, invented a double-eyelid surgical procedure to make Asian eyes look Western, which he ended up testing on Korean sex workers so they could be more attractive to GIs. Now, it’s the most popular surgical procedure for women in South Korea. My ancestral country is just one small example of the millions of lives and resources you have sucked from the Philippines, Cambodia, Honduras, Mexico, Iraq, Afghanistan, Nigeria, El Salvador, and many, many other nations through your forever wars and transnational capitalism that have mostly enriched shareholders in the States. Don’t talk to me about gratitude.

[...]

I could begin writing about buying flowers from the corner deli, but give me enough pages—two, twenty, or one hundred—and no matter what, violence will saturate my imagination. I have tried to write poems and prose that remain in the quotidian, turning an uneventful day over and over, like a polished pebble that glints in the light into a silvery metaphysical inquiry about time. It is late spring. I pick up my daughter from preschool and on our walk home, we admire the perfect purple orbs of onion flowers in bloom. My husband makes dinner that we sometimes take upstairs to our roof with the view of the train and the sun that melts its blood orange into the clouds.

I write down my daily routine that is so routine it allows me the freedom to ruminate. At what cost do I have this life? At what toll have I been granted this safety? The Japanese occupation; the Korean War; the dictators who tortured dissidents with tactics learned from the Japanese and the war. I didn’t live through any of it, but I’m still a descendant of those who had no time to recover; who had no time, nor permission, to reflect.

(from Cathy Park Hong's Minor Feelings)

What if we read the nostalgia in EATEOT Stage 1 as a depiction of some pathologically selective collective amnesia on the part of American society, an attempt to imagine itself as more innocent by trapping itself in a more innocent collection of memories? Without the Cold War paranoia, the segregation and racism, the environmental degradation, the gender structures, the economic instability for auto workers, etc. (i.e. without all the problems which persist in US politics today), perhaps those really were the great days to restore America to. But don't pay attention too closely or else you'll notice the omissions and distortions and ruptures in those memories which have replaced reality as your present - and the hollowness of your beautiful daydream will leak through and you will wake up only to realize how you have irrevocably lost yourself, or else you won't wake up at all. So perhaps EATEOT Stage 1, through the uncanniness of its representation of remembering the happy parts of 1950s America, evokes a kind of horror about American nostalgia built on a selective memory unable to face reality. Even if Andrew Hess did not intend such a reading, I think the fact that his track contains the potential to take on its own life in such a way makes it more interesting.

If EATEOT Stage 1 does anything with its repetition and with the time it asks us to set aside for it, it gives us permission to pay attention, to reflect, and also to let our minds wander as we do so. My review asks you to notice how race haunts this track. But even if you draw a different set of conclusions about the meaning of EATEOT Stage 1, I think your experience of the track will be richer and more meaningful if you accept its challenge to think about what we remember and what we forget.