In the previous post on this subject I tried to explain why the cost to destroy Bitcoin is greater than the security budget, but I did not get into how much greater it may be. A key factor is how much does it cost to use additional signals along with proof-of-work to coordinate between honest miners (not as an alternative consensus mechanism for the Bitcoin network!) and determine what is the most valuable chain tip. Proponents of the security budget argument depict anything other than proof-of-work as heresy, going as far as to warn about the expected destruction of Bitcoin if the use of such signals is ever needed.

The first thing honest miners will do in the event of a censorship attack is to compare their orphaned blocks —and block templates— with those that became part of the heaviest chain, trying to determine what was the cause of the orphaning.

Fig 1. Screenshot from 0xB10C’s miningpool.observer.

Unless the attacker fills his blocks with transactions paying a greater fee than the most expensive transaction in everybody else's mempool, it would be trivial to identify censoring blocks —leading to worthless coins— in an inexpensive way that does not imply any additional trust requirements. Mempool based heuristics require to remain always online, or at least for a certain period of time before being able to flag censoring blocks. But this does not seem like a deal breaker for miners, or for merchants who do not want to wait an extended number of confirmations to validate payments. And it is not something every node would need to do.

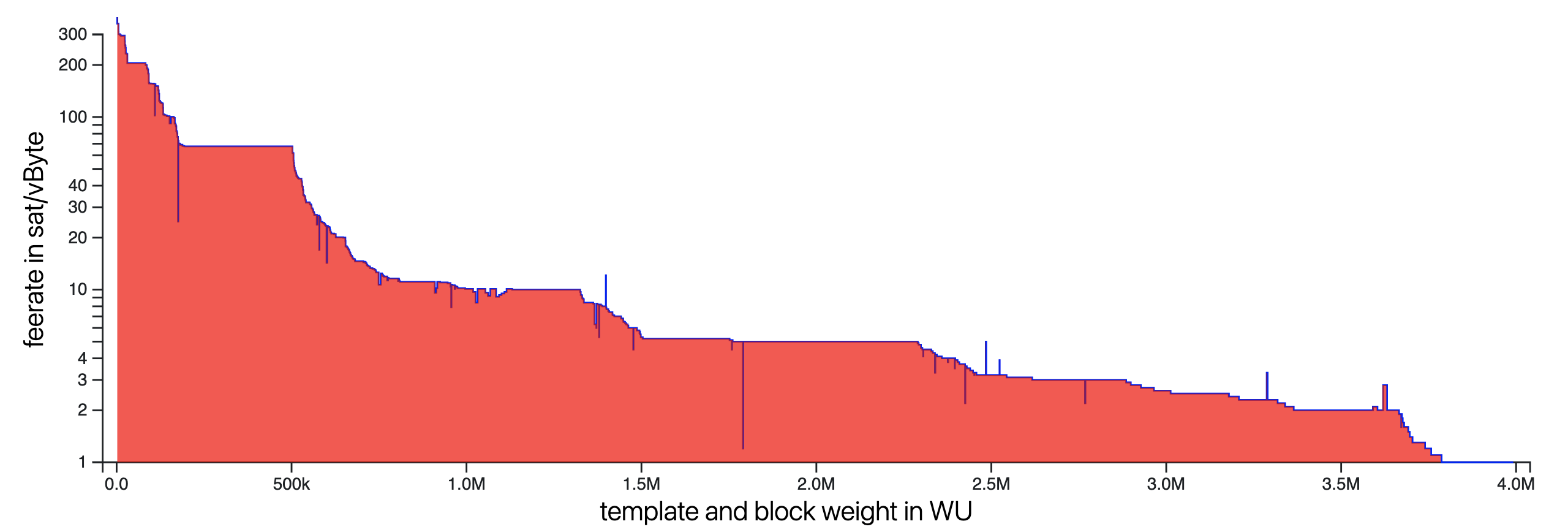

Fig 2. Feerate distribution of transaction packages in a block.

Transactions included in a block only need to pay slightly more than the first transaction that does not make the cut. And, despite this fact, some transactions pay orders of magnitude more just to ensure they are mined in the next block. In the event of a censorship attack, some urgent and valuable transactions would be willing to pay many orders of magnitude more than the average transaction pays when everything runs smoothly, and the latter are what determines the security budget used by some to assess Bitcoin's security.

An attacker trying to hide his censoring blocks would need to fill them all with transactions so expensive that they displace every legit transaction in honest miner mempools. This would cost many orders of magnitude more than the security budget. Not 10 times or even 100 times more. Otherwise his censoring blocks would be trivially flagged. It is crucial to realize that the fees of a few transactions sitting in honest mempools unconfirmed will determine the cost of every block the attacker builds. Honest actors can make the cost of an effective attack skyrocket for a moderate expenditure in fees.

You may be tempted to think that the attacker can pay any amount. After all, he is paying fees to himself. But publishing transactions with expensive fees is not an attack in itself. Once the attacker’s chain is invalidated —because coins in it are worthless and sooner or later the market will agree on a valuable alternative chain— those transactions will be mined in the honest chain and honest miners will get the rewards. There is a real cost in publishing transactions that can effectively conceal the attack.

Note that regular nodes do not need to worry about this. Most nodes are not economically determinant, and they can passively wait for an extended number of confirmations until the attacker switches chains following the market and they see their transactions confirmed. In doing so —following the market to sustain the attack—, the attacker helps to reorg the heaviest but worthless chains he previously built himself. A block at a certain depth will always be part of both the honest chain and the attacker’s one. As long as such a common block keeps advancing, passive nodes will remain able to confirm transactions.

I don't think this is trivial. You cannot use the mempool as an input to a consensus decision. Everyone's mempool is different and an attacker can even groom your mempool through partition attacks to change your view. In general you cannot heuristically invalidate blocks because those heuristics can be observed differently by honest parties.