Last active

August 29, 2015 14:24

-

-

Save georgewsinger/79d5a731f0d10ead5478 to your computer and use it in GitHub Desktop.

Unicorns

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| [TOC] | |

| # Classifying the Unicorns | |

|  | |

| I recently completed my [classification of the Unicorns](https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1qbxPw076NXCniuwCa5-qqkR2eRMlkZgn44WHVwqjpLc/edit?usp=sharing) (henceforth "The List"). I did this for two reasons: (i) I want the patterns of the Unicorns to be flowing through my blood, and (ii) I want to see things from the perspective of the Venture Capitalist, who is generally only interested in the few outliers that [comprise the vast majority](http://www.paulgraham.com/swan.html) of his returns. | |

| <!--**WARNING:** A painful dose of reality follows this point.--> | |

| <!-- | |

| So check it out, and afterwards, you can read some of the lessons that I learned from this classification below. Keep in mind that while every claim I make is subject to exceptions, edge cases, and nuance, many of the lessons are fairly straightforward (and harsh). | |

| --> | |

| <!-- | |

| After all, if *you* don't 100% understand why your company deserves to be on The List, then no one else is going to give you the benefit of the doubt. | |

| PS -- I also added Harold Hamm's Unicorn -- Continental Resourcse -- which was founded in 1967. --> | |

| # 1 Unicorn Products | |

| ## 1.1 Unicorns sell 10x products. | |

| Repeat this to yourself three times over: In order to plausibly make The List, you need a product which is an order of magnitude better than what it is you are trying to displace. | |

| This is highly non-trivial, and something I wouldn't have believed a year ago, so I'm glad I went through the exercise of actually looking at the data myself. While I still suspect this is not the case for the mediocre companies, there's no questioning that it's true for the Unicorns. | |

| <!-- | |

| This terrible mindset is best summed up from Stringer Bell: | |

| https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_4HD1HgfKB4#t=0m44s | |

| Again, it turns out that this mindset doesn't work when it comes to the most valuable companies (although it wouldn't surprise me if it was more true for the mediocre successes). | |

| --> | |

| In fairness, it's true that The List contains *a few* edge cases (coming mainly from companies whose products I don't quite understand) as well as a handful of flat out exceptions (though they are far down in The List in terms of their valuations, and are less than a handful in number). Nevertheless, the frequency of innovative to non-innovative products sits between the following bounds: | |

| $$ | |

| 74.03\% = \frac{57}{77} \le \frac{\text{# of 10x Products}}{\text{# of Unicorns}} \le \frac{73}{77} = 94.81\% | |

| $$ | |

| I conclude that only a fool would think he has a chance of becoming a billionaire with a shitty product. | |

| <!-- | |

| Special mention goes to [Kabam](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabam) (a true bottom feeder company). | |

| --> | |

| Finally, it's worth mentioning the fairly obvious cavaeat that a 10x product doesn't guarantee you a spot on The List. I mean, there are a ton of companies that offer 10x products that aren't worth a billion or more dollars (Wikipedia, Quora, Stackexchange, and so forth). **Creating the best product in the world won't mean anything if you can't effectively monetize it.** Business model issues, distribution strategies, long-term durability: all of these things matter for Unicorn status. **But so does product**, and that's the only point that this spreadsheet establishes beyond any reasonable doubt. | |

| <!-- | |

| As Peter Thiel puts it, to start a billion dollar company you have to *both* (i) create an enormous amount of value and (ii) capture a decent percentage of that value such that you are worth a billion dollars. Even though companies like Stackexchange and Quora are worth a decent amount of money (approximately \$500 MM to \$900 MM, respectively), they don't quite capture enough of their value to reach the billion dollar level. | |

| --> | |

| ## 1.2 Unicorns don't sell pure UX products. | |

| What could be more interesting than what's on this list? Answer: What's *not* on this list. And so far, I haven't caught any companies that made this list purely on the basis of UX (although, if you use that word liberally enough, you could argue that companies like Zenefits would serve as counter-examples, so note that I'm using the word "UX" conservatively). | |

| Now I've earlier claimed that better UX cannot make a 10x product, so it looks like I was right. But, in truth, I was actually looking for counterexamples to this along the way, and was surprised to not find any whatsoever. For example, HipMunk is a pure UX product (under my conservative definition), and for some reason I thought it was going to be on this list. But they're not even worth \$100 MM, much less \$1 BB. | |

| **Conclusion:** Good UX might win you a petty battle, but it's not going to win you a war. Don't think that offering a better color scheme and a cleaner interface is going to net you a $1 BB+ company. | |

| ## 1.3 Unicorns are Last Movers. | |

| There are two characteristics of a Last Mover: (i) they come to the scene extremely early, although not necessarily first and (ii) once they make their move, the market closes. | |

| First, let's talk about the importance of coming early. How do you make a billion dollar consumer eCommerce company? Start one in the late 90s, before eCommerce is even popular (Fanatics). What about a billion dollar sales analytics company (a standard business practice in 2015)? Start such a company in 2004, well before sales people realize that internet data can impact their bottom line. A billion dollar education company? The only one on the list was founded in 2008, before online courses became a thing. **See my point? You're not going to make this list unless you're thinking like an (intelligent) contrarian.** You have to be different (hence early) and right. | |

| Of course, it's a well known phenomenon that first movers can get screwed (think MySpace vs. Facebook). So it's not enough to be onto an early trend; **you have to be the first company to actually solve the problem that the trend is addressing**. You have to be a "Last Mover," as Peter Thiel puts it. | |

| A consequence of this phenomenon is that once the market's Last Mover is crowned, entering their space becomes *stupid*: after consumers start using something (because it actually solves their problem), they become *stuck* to their product, and aren't going to move onto something else *even if* that something else is slightly better (which is why, incidentally, billion dollar companies have to put forth 10x products to begin with). | |

| So it all comes down to the issue of *timing*. If you arrive too early, you risk running a free experiment for the next competitor to learn from (i.e., MySpace ran a free experiment for Facebook). But if you arrive *too late*, you have virtually no chance of creating a billion dollar company. On this issue, check out [this short stream of quotes](https://medium.com/@a16z/success-is-a-question-of-when-not-if-bd1f97580360) from Marc Andreeson (VC and creator of Netscape, a Unicorn from the mid 90s). | |

| ## 1.4 Unicorns don't pivot. | |

| Pivoting is for losers. Or, more precisely: *visible* pivoting is for losers. And this is because less than 5 companies on The List came about as the result of a (publicly noticeable) pivot. Let that (horrific) fact sink in, because it means, approximately, **either you get it right, or you don't.** | |

| Another way of saying this: if the public notices your sudden change of course, then either you *didn't think it through* or you *weren't responsive enough to the early data*. In the former case, you didn't think hard enough about whether your idea was stupid (see the next subsection), so when you end up running into an obvious problem 1 year in, you are then faced with the impossible task of changing the Titanic's course before it inevitably crashes into the iceberg (killing 2/3 of the people on board). In the latter case, it means that you proceeded with a stupid plan for long enough (in the face of negative empirical feedback) that when you *finally decide to change course* (far enough along into the process that everybody notices), it's *too late*. So stay sensitive to early feedback, and (better yet), get it fucking right before you even start. | |

| **The corollary to the theorem that "pivoting is for losers" is that "thinking is for winners."** Here's a [great video](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_GZJdAvciLo#t=13m56s) (it should start at 13m56s) of Reid Hoffman explaining how he eliminated 4 of PayPal's earliest product ideas (3 before they even launched and 1 right after they launched) *purely through thinking them through*. It's an absolute must watch couple of minutes. And here's another quote of him talking about the thinking process again (although not as good as the prior video): | |

| > You have that investment thesis, and you say is my investment thesis | |

| > increasing or decreasing confidence? Do I think that the data that I | |

| > get from the market, when I talk to smart people, how does that change | |

| > my confidence in it? This is how you minimize risks. For example, very | |

| > early days in Paypal, part of what happened was they said they were | |

| > going to do cash and mobile phones with cash on Palm Pilots because | |

| > its really easy. **We actually realized the cash from Palm Pilots** | |

| > **wouldn't work even before we launched the product.** Basically what | |

| > happened I went in and said to Max and Peter, I said here's our | |

| > challenge...the whole use case was splitting the dinner tab and | |

| > everyone at table would have a Palm Pilots budget tab. [But how many | |

| > palm pilot users are there?] Zero to one in every single restaurant. | |

| > **So you could, even by just thinking through the direction you are on** | |

| > **you are going to hit a mine field and you need to pivot.** And that's | |

| > when Max Legend came up with the idea saying action packed sent by | |

| > email. We can have email payments as the backbone of this and we were | |

| > like yeah thats a good idea. Of course that what the whole thing | |

| > pivoted into. And that is part of thinking though minimizing the risks | |

| > as you are executing. | |

| # 2 Unicorn Founders | |

| The following observations were mostly taken from the web. **But they provide a brutal reality check on how crucial the founders and their environment play in the success of a startup.** In fact, team dynamics are so predictive when it comes to startup success that some VCs invest *exclusively* on this metric alone. Yet it's so easy to think "oh, well, me and Craig are *the best*; we're gonna succeed no matter what!" That turns out to be naive. | |

| Delusional confidence is a social skill that's useful when talking to strangers and motivating teams during low periods. [Otherwise, it's your cognitive enemy](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Bo-RA0sGLU#t=2m01s). It wants to see you fail. Millionaire real estate brokers are delusionally confident; billionaire Unicorn founders are not. | |

| <!-- | |

| It might help real estate brokers become comfortable, but it doesn't help you when you're navigating a complex system and trying to find opportunities that millions of other people are missing. | |

| --> | |

| ## 2.1 Over 90% of Unicorn co-founders have *years* of history together. | |

| This is a really important fact, so let this sink in. | |

| More stats: 60% of cofounders worked together in the past, while 46% went to school together. In fact, there's only one Unicorn on the list where the founders didn't extensively know each other beforehand, and that's JustFab. But its two cofounders actually met each other when both of their respective (first) companies were being acquired by the same parent. And even then, this was one of the worst companies on the list (not only did they barely make the list with their low valuation, but they also sell a non-innovative product and compete with Amazon on price, which is stupid since Amazon has always killed off its competition in the long-run -- see [Fab](http://www.businessinsider.com/how-billion-dollar-startup-fab-died-2015-2) as an example, which, as its name suggests, was basically another JustFab with bells and whistles). | |

| ## 2.2 More than 80% of Unicorn founders had *already created a company beforehand*. | |

| This is another astonishing fact, so let it sink in. **Note that even college dropouts had prior experience creating failed companies as early as Jr. High.** | |

| ## 2.3 All but 2 of the Unicorn founders *had prior experience in tech*. | |

| Put differently: if you want to be worth a billion dollars in 7 years, you better know how to code. | |

| ## 2.4 More than 90% of Unicorn founders *had degrees in technical fields*. | |

| Because I'm biased, I'd like to also point out that many of the remaining Unicorn founders had degrees in Philosophy as well (most notably Reid Hoffman and Peter Thiel). Nevertheless, building a billion dollar company seems to require require the sorts of thinking skills that math and engineering degrees cultivate. | |

| ## 2.5 More than 2/3 of Unicorn founders *attended Top 10 schools* (but not Yale). | |

| And there's a power law distribution here as well: 1/3 of Unicorn founders came from Stanford alone, and when you add in Harvard and MIT you reach over *half* of the companies on the list(!). This again shows how important environments are, and how surrounding yourself with toxic people can permanently fuck up your chances of success. For example, it can't *just* be that these schools attract high IQ students, because if that were the case you'd expect other top schools (like Yale and Princeton) to generate an equal number of founders, *but that's not observed*. Anecdotally, the only person I personally knew at Yale that was interested in startups was Matt Brimer. The environment was toxic for this. As far as I know, Yale hasn't generated a single Unicorn founder in the last 20 years. | |

| Finally, I'd like to point out how this statistic runs contrary to my formerly treasured (and yet false) belief that "rich people are dumb". While there is some truth to this, it turns out the reality of the situation is more nuanced: rich people are dumb, but the *richest people* are smart (but also: they are surrounded with the right people, move to the Bay area, and so forth). | |

| ## 2.6 Unicorn founders live in the Bay Area -- *not* New York. | |

| Reality check: the vast majority of Unicorns are founded in the Bay Area, *not* New York. You might have already known this: "of course, I know New York is second to California for innovation, but New York is still on the map, right?" No. Saying New York is second to California for innovation is like saying Albany is second to NYC for population. By one measure, only 5% of Unicorns come from NYC (i.e., a handful of industry specific examples). Generally, this place is toxic for innovation. Unless you have some industry-specific *reason* to be located here, you're at a huge disadvantage. | |

| Local network effects are huge. And environments can make or break success. In my case, who knows if I would even be considering startups if it weren't for the fact that I got to live with an [extremely successful one](http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/01/16/general-assembly-co-founder-matt-brimer-on-creating-communities-with-his-pre-work-dance-party-daybreaker.html) for 2 years. | |

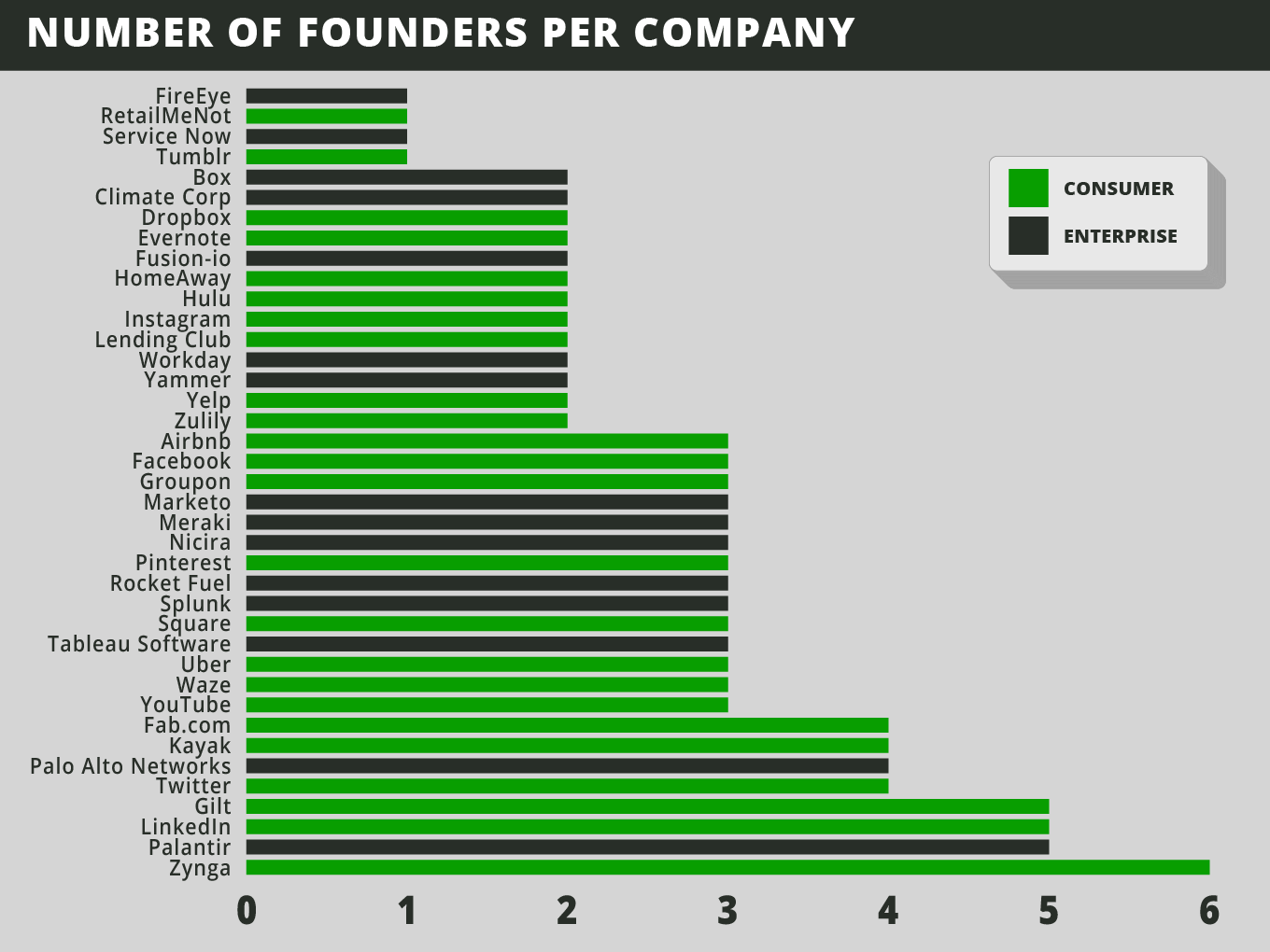

| <!-- 2.7 The average number of founders for a Unicorn is between 2 and 3 people. | |

|  | |

| As you can see, it's not generally smart to start a company alone, nor is it generally smart to start a company with more than 4 people. Although even these outliers I think are explained by special circumstances. In my case, I think I would be more suited to be a solo founder than others. And in cases like LinkedIn and Palintir (which had 5 cofounders), there were so many smart people involved (with decades of prehistory) that it would have been legitimately stupid to start with fewer people. | |

| --> | |

| # 3 Unicorn Statistics | |

| Here is a synthesis of some of the remaining statistics I found online concerning Unicorns. Brace yourself: more reality checking ahead. | |

| ## 3.1 You have a higher chance of catching a foul ball at an MLB game than you do of creating a Unicorn. | |

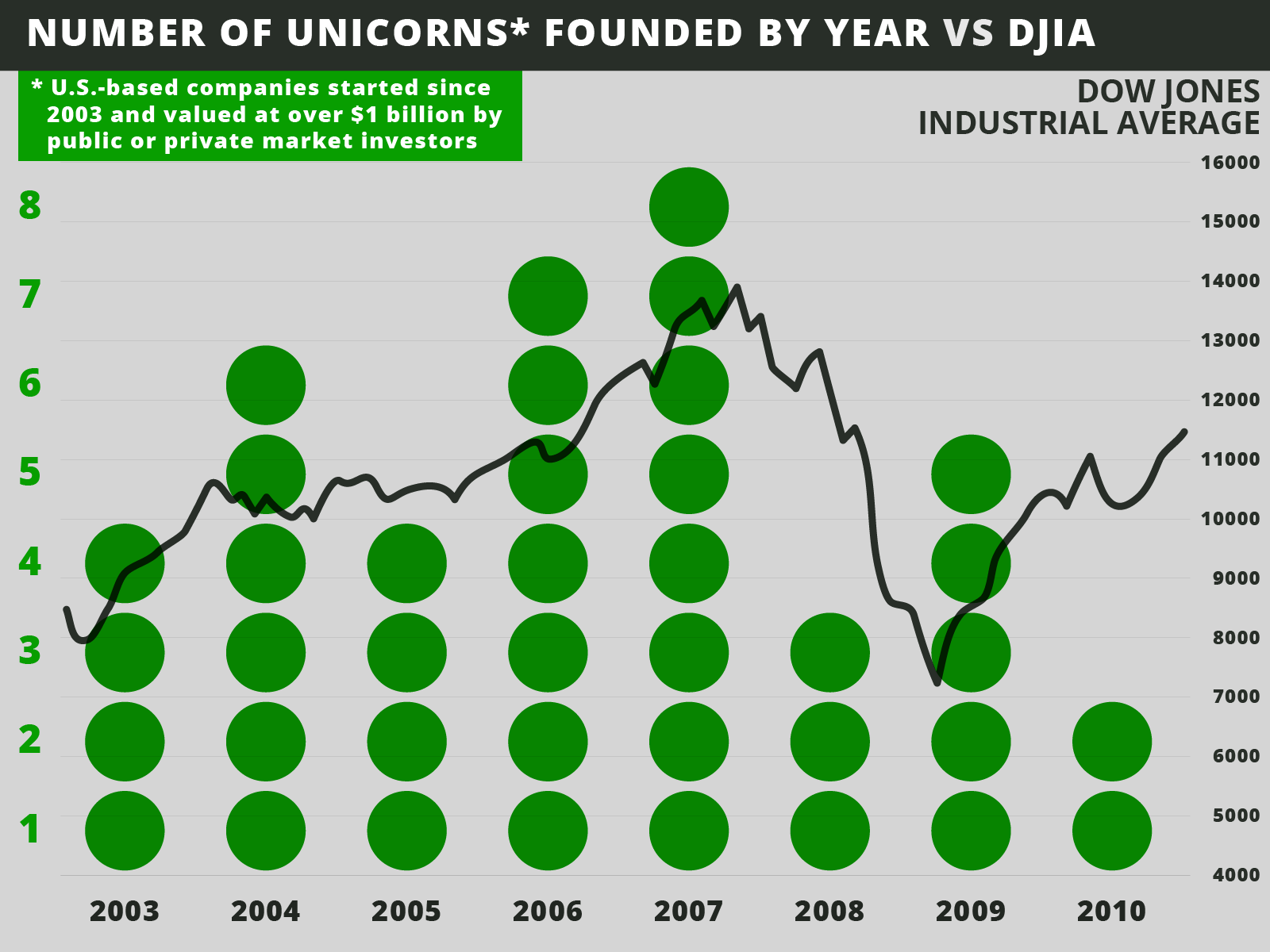

| There are between 10,000-15,000 software/internet companies founded each year. About 4 of these are unicorns. Let's do some math: | |

| $$ | |

| \text{Frequency of Unicorns } = \frac{\text{# of Unicorns}}{\text{# of Startups}} = \frac{4}{15,000} = 0.00027 | |

| $$ | |

| Comparatively, this is lower than your chances of catching a foul ball (which is 0.0012) at a single MLB game. | |

| Here is an old chart from TechCrunch which shows the actual Unicorns created per year: | |

|  | |

| Of course, what this chart *doesn't* show is the **15,000 loser dots** stacked above each year. | |

| ## 3.2 Unicorns follow a power law distribution, making them incredibly counter-intuitive. | |

| You see power law distributions everywhere in nature. Unfortunately -- much like the concept of exponential growth curves -- humans have a hard time understanding them. Here are two examples with respect to the Unicorns specifically: | |

| 1. More than 90% of a VCs investments come from 1 or 2 of their investments (i.e., Unicorns). | |

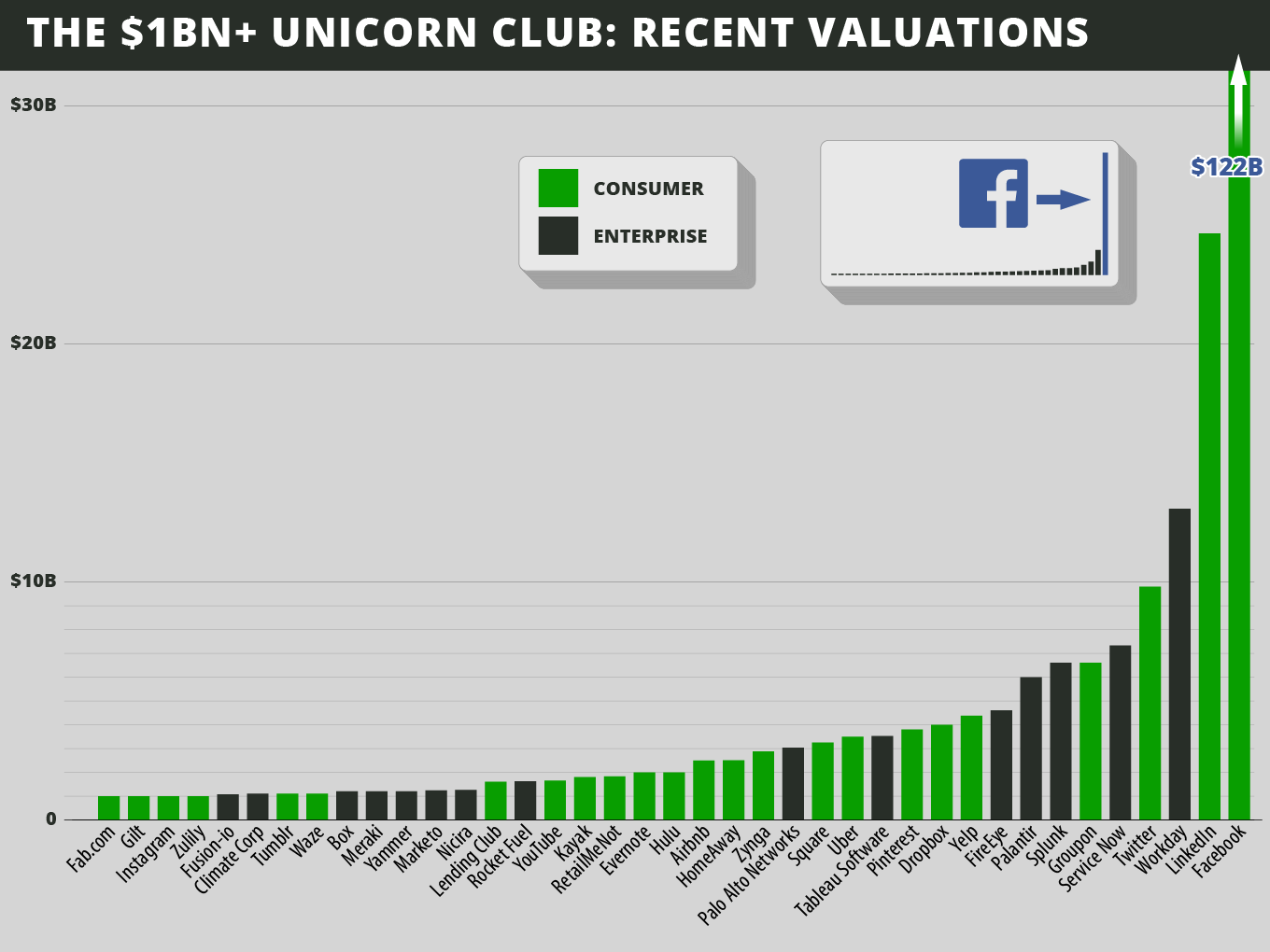

| 2. More than 90% of Unicorn wealth is created by 1 or 2 of the Superunicorns (i.e., the Facebooks, Apples, and Googles of each decade). | |

| An implication of (1) is this: if you're a VC, and you spend 10 long years agonizing over thousands of investment decisions, **less than 5 of those decisions will actually be consequential**. That's why the very best VCs are so paranoid: they literally cannot afford to be otherwise. | |

| An implication of (2) is that, even amongst the very best companies, the vast majority of the wealth is coming from the *winners*. The spreadsheet I made doesn't cover the Superunicorns (i.e., the companies like Facebook and LinkedIn), but if it did, you would see something like the following power law distribution at play: | |

|  | |

| Roughly, each decade yields 1-2 Superunicorns. The 2000s gave us Facebook. The 1990s gave us Google and Amazon. The 1980s produced Cisco. The 1970s birthed Microsoft and Apple. And in the 1960s, we had Intel. | |

| ## 3.3 But it's even worse: Going for a Unicorn *decreases* -- not increases -- your chances of achieving a marginal success. | |

| You might think that trying to build a Unicorn is harmless in the following sense: "if I shoot for Mars, odds are, I'll at least make it to the moon!" But this is wrong, because it assumes that the probability of a big success is some constant fraction of the probability of a marginal success. Unfortunately, the reality is that shooting for Mars means you'll either make it there safely, or everyone on board your spacecraft will die. As Paul Graham puts it: | |

| > "The fact that the best ideas seem like bad ideas makes it even harder | |

| > to recognize the big winners. It means the probability of a startup | |

| > making it really big is not merely not a constant fraction of the | |

| > probability that it will succeed, but that the startups with a high | |

| > probability of the former will seem to have a disproportionately low | |

| > probability of the latter." -- Paul Graham | |

| This gives rise to Peter Thiel's famous Venn Diagram. | |

|  | |

| I actually didn't realize this a year ago, but this diagram **only applies to the Unicorns**; marginal successes are actually easy to predict by knowledgeable outsiders. Unicorns are not. | |

| <!-- | |

| "The probability that a startup will make it big is not simply a constant fraction of the probability that they will succeed at all. If it were, you could fund everyone who seemed likely to succeed at all, and you'd get that fraction of big hits. Unfortunately picking winners is harder than that. You have to ignore the elephant in front of you, the likelihood they'll succeed, and focus instead on the separate and almost invisibly intangible question of whether they'll succeed really big." -- Paul Graham | |

| --> | |

| ## 3.4 Unicorns take an average of 7 years to make their founders rich. | |

| Ok, this is actually the good news. It takes, on average, 7 years for an exit (with enterprise companies taking about a year longer than consumer companies). Here's a picture of Peter Thiel after he exited from PayPal. It took 4 years from start to finish. | |

|  | |

| The little kid on the right is worth 9 figures. | |

| <!-- | |

| This is the main reason why I'm interested in startups. I want to take care of the money problem while I'm young, and then do more interesting things afterwards. | |

| --> | |

| # 4 Unicorn Skill | |

| Creating a Unicorn is a matter of skill, not luck. How could I possibly say this after all that I've written above? The answer is that there are too many people who have started more than one Unicorn in their lifetime (more, that is, than could possibly be explained by chance). | |

| Of course, it might be objected that founders who start multiple Unicorns are merely lucky. After all, with a big enough population (and over a long enough time horizon), all sorts of unlikely things eventually occur. But the population of Unicorn founders is too small -- while the number of Unicorn multi-founders too big -- for this to be the case. | |

| It is analogous to coin flipping: if millions of people started flipping coins endlessly, eventually we would expect for one of them to reach a 1 million long streak of heads. But if, upon sampling 100 or so coin flippers from this population, we found that a dozen of them achieved such a feat several times in a row, we would **instead be justified in concluding that their coins were rigged**. This is a mathematical consequence of [Bayes' Law](%28https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayes%27_theorem%29). | |

| The most badass examples of Unicorn multi-founders come from the "PayPal Mafia," shown below (this picture was taken as a joke for a magazine cover). | |

|  | |

| Peter Thiel (bottom-left) puts it like this: | |

| > "The first team that I built has become known in Silicon Valley as the | |

| > 'PayPal Mafia' because so many of my former colleagues have gone on to | |

| > help each other start and invest in successful tech companies. We sold | |

| > PayPal to eBay for \$1.5 billion in 2002. Since then, Elon Musk has | |

| > founded SpaceX and co-founded Tesla Motors; Reid Hoffman co-founded | |

| > LinkedIn; Steve Chen, Chad, Hurley, and Jawed Karim together founded | |

| > YouTube; Jeremy Stoppelman and Russel Simmons founded Yelp; David | |

| > Sacks co-founded Yammer; and I co-founded Palantir. Today all seven of | |

| > those companies are worth more than \$1 billion each." | |

| I'm honestly interested in how someone could think this is a "fluke" given the argument above. The collective IQ at the above table is north of 2,000. Most of them went to Stanford (steeped in early startup culture), had known each other for years (i.e., long prehistory), had other startups under their belt, and then lived together in the Bay Area for half of a decade doing nothing but intensely learning how to build a Unicorn from scratch. | |

| There's more to it than this. Their fate was not determined by their correlations (nor is yours). But it can't be luck. Unicorns can be built with skill. |

Sign up for free

to join this conversation on GitHub.

Already have an account?

Sign in to comment